Puritan alchemists founded America; sounds like bad fiction but it’s fact. As befits a young republic, the history of the earliest origins of American Metaphysical Religion amounts to a long list of extraordinary characters, daring experiments, and unlikely friendships. We’ll meet alchemists who persecuted witches, alchemists who were governors, and several alchemists who served as presidents of the first American colleges. The community of alchemists at home and abroad was in constant touch with each other, eagerly exchanging techniques, results, and useful writing published and unpublished. At the heart of this vital cosmopolitan movement for cultural evolution were the intelligencers, discerning men who were so respected they became gatekeepers. By exchanging letters (sometimes in secret codes), samples, and books with fellow seekers of knowledge across continents and oceans they became the Internet hubs of their day. If a valuable discovery was made in a far off land, news of it would soon be all over the world thanks to the intelligencers.

Puritan alchemists founded America; sounds like bad fiction but it’s fact. As befits a young republic, the history of the earliest origins of American Metaphysical Religion amounts to a long list of extraordinary characters, daring experiments, and unlikely friendships. We’ll meet alchemists who persecuted witches, alchemists who were governors, and several alchemists who served as presidents of the first American colleges. The community of alchemists at home and abroad was in constant touch with each other, eagerly exchanging techniques, results, and useful writing published and unpublished. At the heart of this vital cosmopolitan movement for cultural evolution were the intelligencers, discerning men who were so respected they became gatekeepers. By exchanging letters (sometimes in secret codes), samples, and books with fellow seekers of knowledge across continents and oceans they became the Internet hubs of their day. If a valuable discovery was made in a far off land, news of it would soon be all over the world thanks to the intelligencers.

As Jon Butler wrote: “American colonists had an ambivalent relationship with Christian congregations. After about 1650 even in New England only about one-third of all adults ever belonged to a church. The rate was lower in the Middle and Southern colonies, and on the eve of the American Revolution only about 15 percent of all of the colonists probably belonged to any church. In 1687 New York Governor Thomas Dongan wrote that settlers there usually expressed no religious sentiment at all or, when they did, entertained wildly unorthodox religious opinions.” “Two years before the Salem trials, Cotton Mather was so concerned about the number of settlers who used occult techniques for curing illnesses and settling quarrels that he described the Christian defense against them in occult terms–as amulets–so readers could more readily understand him.” What were these wildly unorthodox beliefs? Jon Butler continues: “American colonists were indeed religious, but many resorted to occult and magical practices unacceptable to most Christian clergymen and lawmakers.”

Lewis Morris, a politician from New Jersey, wrote in 1702 about his constituents: “except in two or three towns there is no face of any public worship of any sort but people live mean like Indians.” The traveling Anglican minister Charles Woodmason reported that in the southern colonies the locals didn’t have a Bible among them. They didn’t want preachers or churches complicating their lives but they did ask to have their children baptized, just in case?

America, the spawn of England, reflected the mother country’s religious diversity. After all, Isaac Newton practiced alchemy. Chaucer, Shakespeare and Milton littered their creations with astrological references. A small percentage of especially clever or daring nobles had always been fascinated with druids, alchemy, astrology, and the occult. The middle class regularly produced some paragon of independent scholarship like Thomas Taylor, the devoted translator of ancient Greek philosophical and religious works. Or theorists of grand spiritual unities like Godfrey Higgins who wrote The Celtic Druids to prove that the first druids were Asians who had traveled all the way to Great Britain. Or General James Furlong whose The Rivers of Life includes a room sized fold out map that attempts to graph a timeline of every religion and cult in history. These polyglot efforts to envision the entirety of the human experience of religion throughout history more than made up for their inaccuracy with their boundless and glorious flights of imagination. They can be enjoyed for their unintentional fictions as marvelous as the work of Borges, yet true gems of fact and interesting insight into history coexist with the accidental fantasies.

As for the poor they had their cunning folk and fortunetellers to help them find the things and people they lost, to pick wedding dates, reverse a trend of bad luck, or most of all heal a sickness or injury. To America came nobles with libraries, free thinking rogue scholars, and cunning men and women. Witchcraft was strictly prohibited, but occultism was a sport of intellectuals, and homespun cures and traditions weren’t considered pagan. Almanacs filled with astrology and bits of occult information were popular back home and abroad. Books on the Cabala, the writings of Hermes Trismegistus, the medical and metaphysical works of Paracelsus were circulated amongst well read citizens in England and the colonies. Not that the English and Americans were rejecting Christianity, they simply had a much wider definition of it than we do today. They didn’t view the wisdom of the ancients as satanic, nor did they fear astrology or think experiments in communicating with spirits or foretelling the future punishable offenses against their faith. If anything by broadening their understanding with the accumulated wisdom and time-honored practices of other cultures, many believed they were becoming better Christians.

But America wasn’t immediately fertile soil for alchemy, astrology and other pagan preoccupations. The desire for religious conformity was a constant force to be reckoned with. Generation after generation of Americans facing this force moved deeper into the wilderness in search of freedom of belief. The American forests were not like the pagan woods of Europe and Great Britain, everywhere haunted by half forgotten sacred sites and magical natural settings. America was nothing but dangerous wilderness. Wandering in the wilds wasn’t mysterious, it was terrifying, and superstition, like smallpox, was epidemic.

FRENCH ALCHEMISTS IN EARLY COLONIAL AMERICA

The Huguenot Cross

Alchemists lived in a world where every thing not only had soul and life but also the desire to evolve. The soul in a lowly chunk of lead was longing to become gold over time, but the alchemist could make it happen much faster. These ideas cultivated by the Neoplatonists, reanimated by Ficino and the Florentine renaissance took full force in the writing and example of Paracelsus the Swiss genius who fathered what would become pharmaceutical science. He was the Luther of medicine, who coined the term “ylaster” or star stuff, to describe what matter and hence humans are made of. In his work sympathies and antipathies, attraction and repulsion, the harmonies of correspondences became laws of spirituality and medicine alike. Paracelsus thought not only that to understand the book of nature you must walk its pages with your feet, but also that the alchemist must be pure, all the vices must be confronted and conquered before the alchemist could expect to be blessed with success. So these early scientists had something of the medieval knight about them. Only the purest of heart could achieve the grail.

Keep in mind that alchemy has been many things to many people, then as now. A hundred years later a clear line would be drawn between the failures of alchemy and the successes of the new science of chemistry. Not long after alchemy would find itself next to palm reading, astrology, and witchcraft as a discredited but romantic art still capable of inspiring artists and occasionally sincere practitioners. General Ethan Allen Hitchcock would argue around the time of Lincoln that alchemy was all metaphor; the real art was a spiritual transmutation, led by the desire to look deeply into the marvels of the divine creation. This became a popular approach for writers from Blavatsky to Manly P. Hall and beyond. Jung took it even further as he proposed a collective unconscious and made of alchemy something like the arrival of pure religion fresh from the unconscious. Eliade believed alchemy was based on the idea that all matter is living and ensouled. Base metals were not inert, lifeless elements. They were living and could therefore grow. Just as Jesus Christ can turn a soul from shadow to light, Eliade said the alchemists reasoned, the right process could turn lead to gold. To perfect the self would lead to perfecting metals.

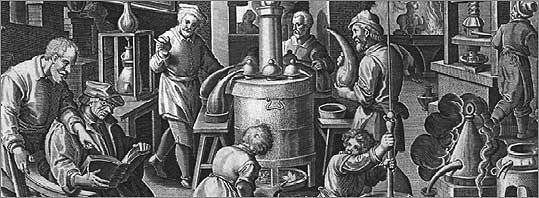

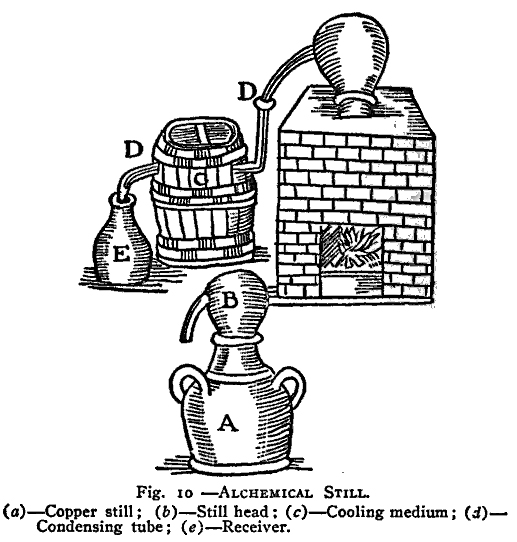

Today historians point out that the laboratory and the practice of chemistry were central to alchemy. In seventeenth century colonial America alchemy was an intoxicating combination of real chemistry, experimental mysticism, and wealth speculation all at the same time, but the most important was chemistry. In fact, some who have been called alchemists had no interest in a spiritual practice at all. They were chemists before chemistry was a science.

On three ships the first Huguenots, and probably the first alchemists in the new world, arrived in 1564, 56 years before the Mayflower. They were weary of the never-ending war between Protestants and Catholics back home. Near what is now Jacksonville, Florida with the help of a local tribe they built triangular Fort Caroline. They were probably the first Protestants to celebrate a thanksgiving in America. But Spain had already claimed Florida and most of everything else in America.

The moat around what’s left of Fort Caroline

The moat around what’s left of Fort Caroline

When the King of Spain heard about the Huguenot fort he sent an army to erase them and replace them with the Spanish colony St. Augustine. The Huguenots courageously sailed out to attack the Spanish at sea but a hurricane dashed their ships against the Florida coast. The Spanish quickly took the fort. Survivors were offered conversion to the Catholic faith. Almost every Huguenot refused, so they were killed. Only a few artisans whose skills were needed and a couple of Catholics who had lived among the Huguenots were spared, less than ten out of three hundred survived. What was their great sin? They were Protestants. They had their own symbol of the cross. They criticized the Catholic sacraments as obsession with death and the dead.

In 1568 in the great walled city of La Rochelle in France, the rebellious Huguenots celebrated victory. The Catholic Church eager to absorb, annihilate or at least expel them had been defeated. The siege was over. The Reformation was the new world order. But not for long. In what became known as the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572 Catholics killed thousands of Huguenots in Paris. Other massacres of thousands in other towns followed until La Rochelle was under siege again. By 1628 the fortress of the Huguenots was a smoking ruin, and most of the inhabitants were dead, killed by the armies of the Catholic counterreformation.

So much war had created an underground of green men, or leaf men, people who had gone mad, who lived in caves, in the woods, creeping through the leaves with matted hair like fur, people who had devolved into wildness. When the Huguenot leaders, or heretics as they had been judged, were marched away to their deaths they were “dressed up in greenery as objects of ridicule.” The proud natural philosophers were reduced to the appearance of mentally ill pagan throwbacks.

Many of the survivors fled to the new world, to workshops in the wilderness, where they could pursue their arts without fear of Catholic persecution. The Huguenots like so many after them were refugees of war who came to America to start new lives. In New York and New Amsterdam they became French craft workers, especially skilled furniture makers, who sought security in their lives by applying in every way they could the principles of Paracelsus, as described in great detail by Neil Kamil in his masterpiece of historical scholarship, the thousand page Fortress of the Soul: Violence, Metaphysics, and Material Life in the Huguenot’s New World, 1517-1751.

Among the earliest to arrive in America, the Huguenots brought with them Paracelsian medicine and alchemical preoccupations. They wanted to live self sufficiently, with freedom of belief, relying on their crafts to survive. Their politics and spirituality were local. They had learned from Boehme to think of life as the art of balancing God’s wrath and love, called by some communities the masculine and feminine, until they were in proper ratio our world would be fallen instead of a paradise. The books written by their spiritual leaders, who were often craftsman, like the great Huguenot rustic ceramic artist Bernard Palissy, were carefully read by reformers in the colonies, including John Winthrop Jr. and Ben Franklin. The Huguenots assimilated quickly into American Protestant culture becoming an important ingredient in the melting pot. Paul Revere was the descendent of Huguenots.

ROSICRUCIAN INFLUENCE ON EARLY AMERICA

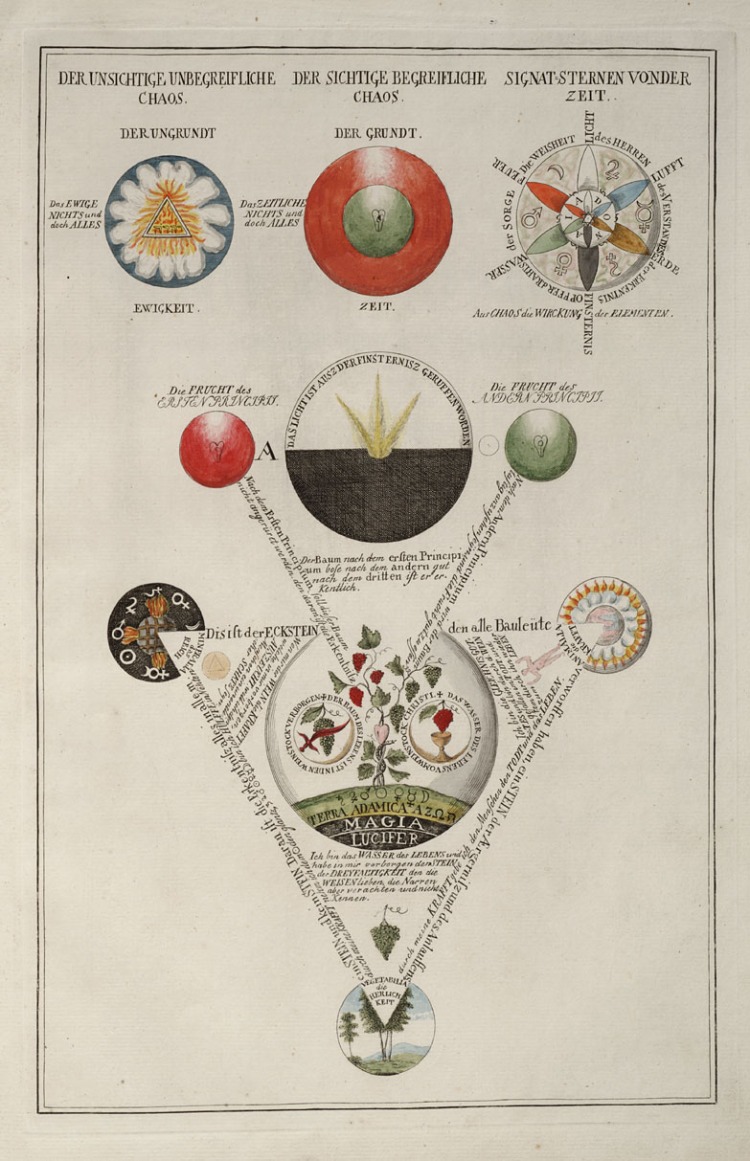

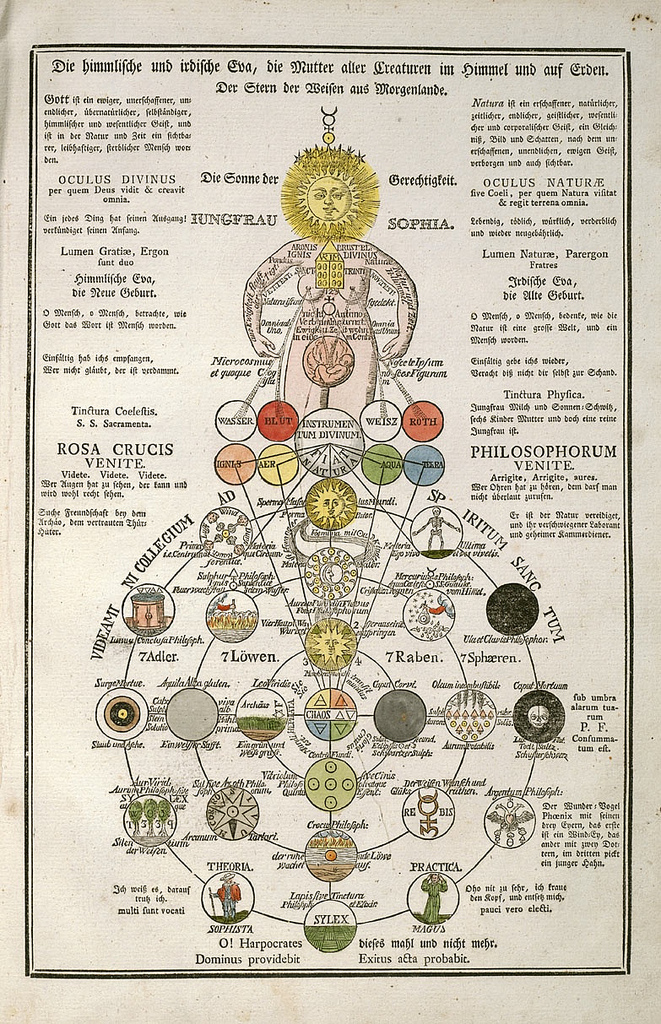

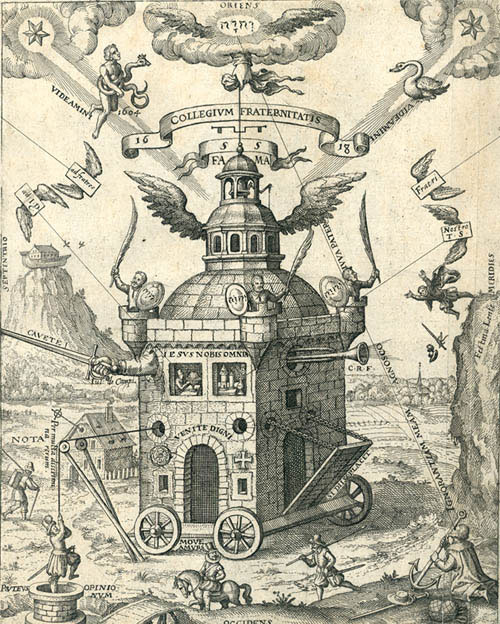

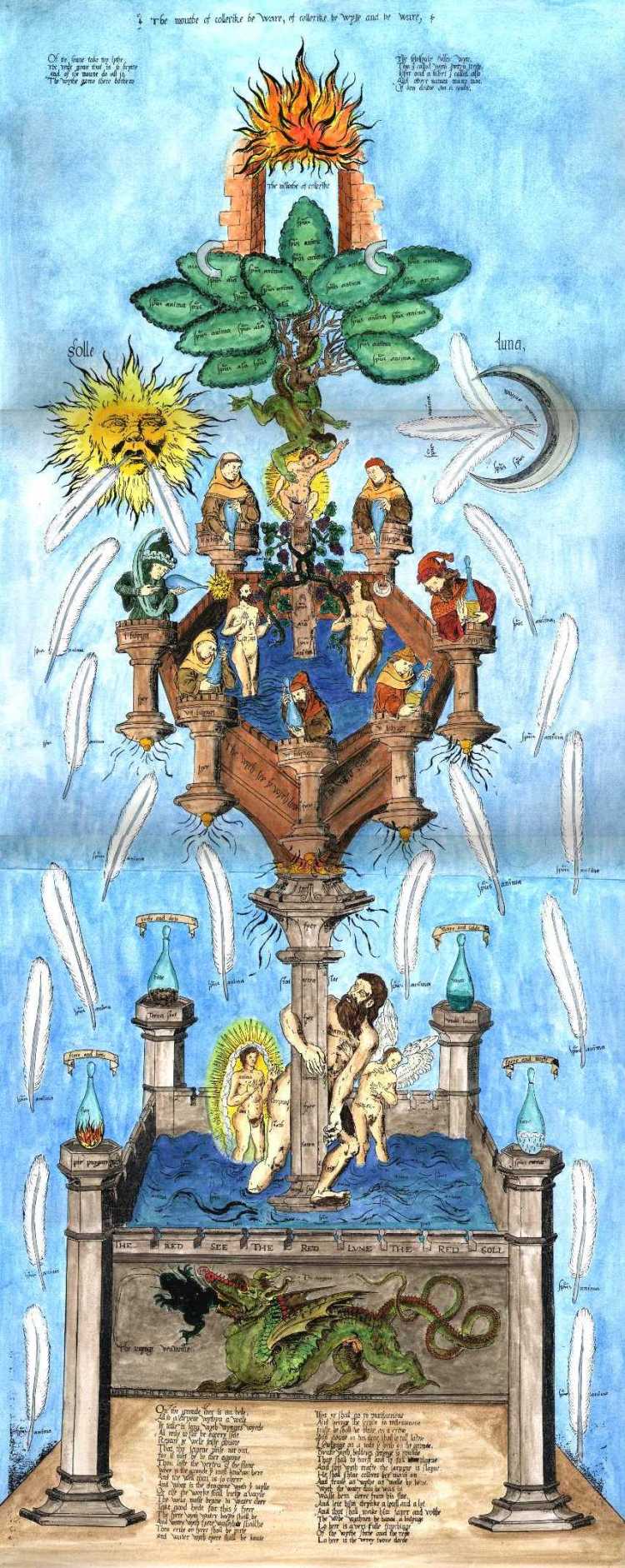

The Invisible College of the Rosicrucians, notice Noah’s ark perched precariously in the distance.

The Rosicrucian contribution to culture is shrouded in secrecy and misinformation. The Rosicrucian manifesto called for “Universal and General Reformation of the whole wide world.” This idea of an invisible college of spiritually superior human beings benevolently conspiring for the good of humanity to this day catches up novices on the spiritual path, giving them visions of adepts materializing before them like Madame Blavatsky’s telepathic masters. On the one hand scholars like Frances Yates have argued persuasively that a genuine Rosicrucian movement existed, including a variety of secret societies with shared goals. More recently most scholars have taken the position that the Rosicrucians were more like a literary movement, but based on the experimental practice of alchemy as a quest for breakthroughs in medicine, metallurgy and what would become chemistry. Telescopes and alembics were holier than sacred relics to these men and women. And women there were, in the chemistry labs, mothers, wives; a book that no one has been able to find but was referenced by Charles Heckethorn in his dated but once seminal Secret Societies of All Ages and Countries was titled Sisters of the Rosy Cross; or, Short Discovery of these Ladies, and what Religion, Knowledge of Divine and Natural Things, Trades and Arts, Medicine. (1620).

The Rosicrucians had announced in their initial publications that they would stay invisible for one hundred years but interested parties should publicly declare themselves and if worthy they would be asked to join the order. This invitation triggered a wave of publications, not only from volunteers wishing to be chosen, but also from critics attacking the Rosicrucian order, and apologists defending it though they were not actually members of it. The most enthusiastic seekers traveled. Following the ideal of Paracelsus, they sold their books, their possessions, and their estates and traveled to every mountain, valley, desert, lake and forest where they were to seek understanding about every plant and animal they encountered. They were to collect recipes from locals and learn the lore of cures. Only then were they ready to buy a furnace and work with the fire that would help them resolve, dissolve and coagulate, taking matter apart, purifying it, discovering hidden properties. And if they were devoted enough, and pure of heart, they would be blessed by the divine with cures and other boons for humanity.

Rosicrucianism was a cultural flowering, both rational and irrational, that arose partly around the misinterpretation of King James of England giving his daughter Elizabeth in marriage to Frederick the King of Bohemia. Reformers saw the marriage as an alliance between England and the various German kingdoms against the Catholic Church, which was patiently planning to reclaim dominion over northern Europe and Great Britain. A prince and princess who fell in love at first sight, the royal couple captured the public’s imagination. Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream was performed for their wedding. All the best minds of science and theatre surrounded them. Back home Frederick built gardens with mechanical statues that whistled for the amusement of his bride, but to the horror of local Catholics who dubbed the garden The Gate to Hell.

The situation was complicated by the death of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, the heir to the English throne. Elizabeth’s older brother was a passionate Protestant who thought his father a peculiar old fogey. Henry was bright, cultured, an athlete, the very incarnation of what the people hoped a king would be, and he was eager to make war on the Catholic powers. Like his beautiful sister he seemed less a Stuart than a Tudor. Tragically a swim in the polluted Thames infected him with typhoid fever. Just before the wedding of his little sister to the German prince who could have united Germany to join England in an alliance strong enough to resist even Rome, Prince Henry died. The wedding festivities continued, but despite the best efforts of Shakespeare, and the dazzling theatrical inventions of Inigo Jones, melancholy pervaded the proceedings. Still, the newlyweds were in love as they journeyed to their fate.

Bohemia was already a symbol of the avant-garde and off beat thanks to the alchemical court of Emperor Rudolf II. Reformers, alchemists, astrologers, inventors like Jones, Paracelsian doctors, mystics of every stripe all assembled at the court of Bohemia where the royal alchemical couple were believed to be presiding over the dawn of a new world order. But not for long. Frederick made the mistake of claiming the job of emperor when it was unwisely dangled before him by his rash allies who were foolishly counting on James. James didn’t like war. His decision not to support his own daughter was very unpopular with the lords and with the people of England who loved their beautiful golden haired princess. They had hoped she would be a second coming of Queen Elizabeth. But without his father in law’s help, Frederick lost his credibility in the eyes of his German allies who left him to the tender mercies of the Pope’s imperial army. In 1620 Bohemia was burned, pillaged and left to the plague. Protestants officials were publicly executed, and their lands and possessions were given to loyal Catholics.

But what of all these reformers of science and education, and the writers promoting imminent utopias? What of the secret societies devoted to the grand project of creating a culture where the best resources could be focused on research colleges instead of war between Christians? What of the alchemists and their dreams of new sciences of health and wealth? With their dream of a Rosicrucian Europe shattered where could they turn their attention? Europe they knew would be embroiled in war. America beckoned, and authors from Sir Francis Bacon to obscure Rosicrucian apologists began enshrining their visions in the new world. Even if they were as loose and unofficial a band as the beat poets of the 1950s, these alchemists and pseudo Rosicrucians stamped their image indelibly on America.

Bacon himself has been often accused of being the leader of the Rosicrucians. Thanks to Manly P. Hall’s guidance, in his collection I encountered two examples of the mysterious hints that have inspired Bacon and Rosicrucian scholars. The first is a copy of the 1660 edition of The Anatomy of Melancholy. On page 62 of the introduction a curious footnote reads: “Joh. Valent. Andreae, Lord Verulam.” Andreae was the reputed author of the Fama and the Chemical Marriage, the books that sparked the Rosicrucian revolution. Francis Bacon was the first and only Lord Verulam of that time. The other hint comes from Mathematical Magic, a book by John Wilkins, a friend of Francis Bacon. On page 237 of the edition published in 1680 where ever burning lamps are discussed, Wilkins makes this provocative statement: “Such a lamp is likewise related to be seen in the sepulcher of Francis Rosicross, as is largely expressed in the confession of that fraternity.” Wilkins equates Francis Rosicross to Christian Rosenkreuz, legendary founder of the Rosicrucians. Were these errors, or subtle hints at a deeper involvement by Bacon in Rosicrucian matters? Since Rosicrucians would never talk about being Rosicrucians the absence of evidence in Bacon’s own writing offers no obstacle to the enthusiastic. Yet, Bacon’s own writing certainly shared most of the Rosicrucian goals.

THE ALCHEMICAL GOVERNOR OF CONNECTICUT

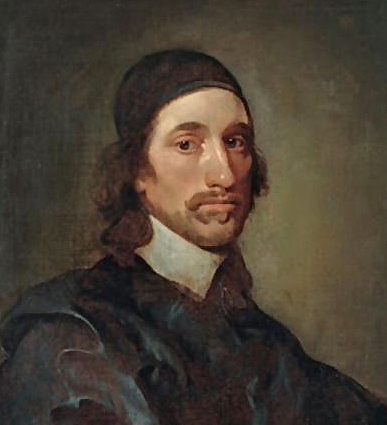

Extraordinary American John Winthrop Jr.

Extraordinary American John Winthrop Jr.

For John Winthrop Jr.’s funeral American poet Ben Tompson wrote a poem that has much more to do with alchemy than Puritanism.

Projections various by fire he made

Where Nature had her common Treasure laid

Some thought the tincture Philosophick lay

Hatched by the Mineral Sun in Winthrops way,

And clear it shines to me he had a Stone

Grav’d with his Name which he could read lone–

His fruits of toil Hermetically done

Stream to the poor as light doth from the Sun.

The lavish Garb of silks, Rich Plush and Rings,

Physicians Livery, at his feet he flings.

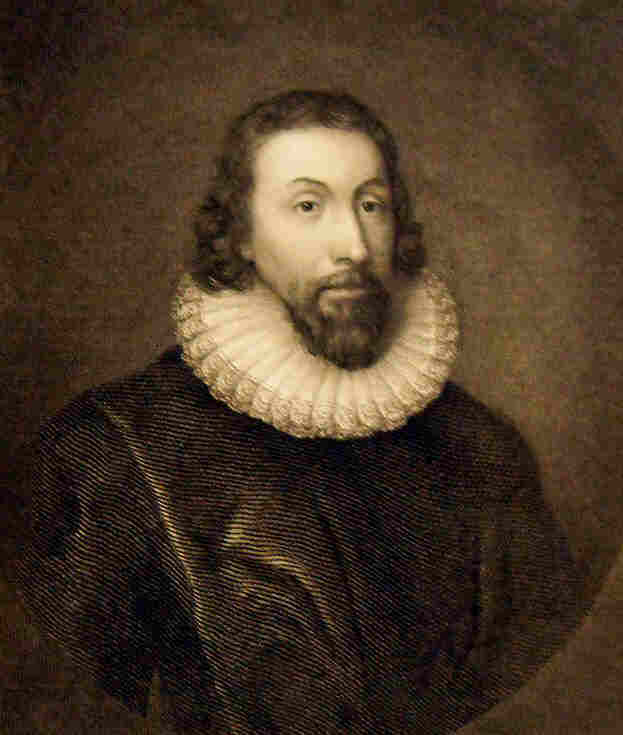

John Winthrop Jr., another important American born on Feb. 12, was not only the most popular alchemical physician in colonial America, he was also the first governor of Connecticut, and a charter member of the Royal Society. An avid astronomer, his three and a half foot refractor was one of the first telescopes in America. The son of the three-time governor and founder of Massachusetts Bay Colony, he tried several times in his life to reach the Rosicrucians, and he patterned his life after their example.

Winthrop first encountered alchemy and the Rosicrucians when he went to school in London in 1624 just after turning eighteen. Within months he and his roommate and lifelong friend Howes were skipping classes to conduct alchemical experiments, and searching for Rosicrucians. Winthrop was so inspired by the example of Christian Rosenkreutz he tried to use his family connections to imitate the founder of the Rosicrucian order by traveling to Turkey in search of alchemical wisdom. Any well-educated European knew that the teaching of alchemy had been preserved and developed by the Arabs. From them came the copies of alchemical classics long forgotten in Europe. But the Arab view of alchemy was thought to be somehow tainted by Islam, which was not the pure truth of Christianity.

Unable to find passage to Turkey in 1627 Winthrop took a position as Captain’s secretary on a ship in the fleet England sent to relieve the siege of the Huguenot fortress La Rochelle. Winthrop hoped that after the battle he might find a boat headed for Turkey. Instead he witnessed the humiliating defeat that left half the English fleet burning, an experience that may explain why as governor he never considered war an appropriate policy. And whenever the king asked him to send soldiers to a war Winthrop would praise the cause and urge his fellow colonial leaders to send troops, while finding numerous valid reasons why his own men could not be in attendance. But Winthrop’s trip to La Rochelle wasn’t a total loss. He met Cornelius Drebbel, an alchemist, physician, and inventor who had been a court favorite of Henry, Prince of Wales, for having built a camera obscura (a device that projects its surroundings on a screen), early microscopes and a submarine that was successfully tested in the Thames. Drebbel mentored Winthrop, and left a fond impression. On the flyleaf of a copy of Basil Valentine’s alchemical classic Of Natural and Supernatural Things Winthrop wrote: “This was once the book of that famous philosopher and naturalist Cornel Drebbel. He usually carried with him in this pocket and after his death was given me by his son in law.”

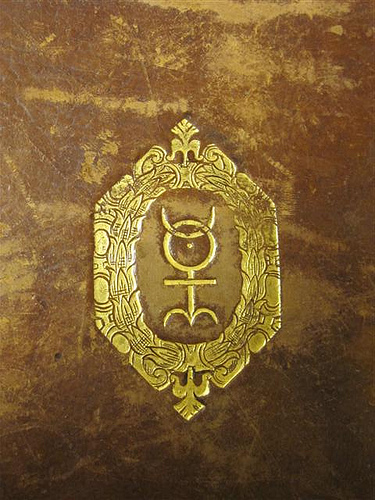

In summer of 1628 Winthrop took a ship to Leghorn, Pisa, Florence and finally Constantinople. Unsatisfied, he planned to travel to Jerusalem, further east, as Christian Rosenkreutz had done, but rumors of war were everywhere. On the return voyage home the following year in Venice, Italy Winthrop met a Dutch scholar returning from a tour of Turkey where he acquired rare Arabic and Persian manuscripts. Two weeks after his son’s return to London, Winthrop Sr. became leader of the Puritans who would colonize New England. WInthrop helped his father sell off their property; he married, but also found time for alchemical experimentation. Winthrop had become fascinated with John Dee whom many have credited as being one of the principle inspirations to the Rosicrucian counterculture. Winthrop began collecting books and manuscripts that had belonged to Dee. Winthrop adopted Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica as a personal insignia, drawing it next to his signature in alchemical texts and using it to mark crates of instruments and chemicals headed for America. It’s an extraordinary image. The symbol invented by John Dee, Queen Elizabeth’s court astrologer, to represent the reformation of the world, an inspiration to the Rosicrucians, often seen in their books, was the emblem painted on the boxes of alchemical supplies imported by the son of the founder of Massachusetts Bay Colony, like Led Zeppelin’s mysterious sigils on their anvil cases.

John Dee’s Monas Hieroglypica

In November 1631 cannons and muskets saluted Winthrop’s arrival in the new world with his new bride. Woodward summarizes the accomplishments that followed. “Over the next half century, Winthrop would found three colonial towns, serve as Bay Colony assistant for nearly two decades, govern the colony of Connecticut for eighteen years, secure that colony a charter from the Restoration court of Charles II, granting it virtual independence, found several New England iron foundries, serve as physician to nearly half the population of Connecticut, and become a founding member of the Royal Society. Alchemical knowledge and philosophies factored, often essentially, into each of these accomplishments.”

As soon as he arrived Winthrop set up an alchemical laboratory in his father’s house. There was nothing wrong with practicing alchemy in an elite Puritan household. Winthrop assisted his father and others governing Massachusetts Bay Colony. He flourished, but his wife did not. Returning to London in 1634 after her death, he and his college roommate Howes were eager to meet Dr. John Everard, a minister and alchemist, a friend of Robert Fludd, and the rumored leading candidate for an actual Rosicrucian. In 1650 Everard would be the first to translate into English the pagan classic The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus. But Everard answered Winthrop’s questions with poetic generalizations. Winthrop and Howes were unimpressed.

Winthrop returned to Europe in 1641 to raise money for an ironworks in New England, arriving at the same time as Comenius, who did impress him when they met. The great educator and philosopher was celebrated for going beyond the utopias of Bacon and Campenella; New Atlantis and City of the Sun were lovely myths but impractical guides to real world challenges. Comenius synthesized the idea of Universal Reformation into some practical suggestions. First, he wanted to establish universal education for men and women. Not everyone would become a scholar but everyone would know how to write and do math. Today it’s hard to imagine how radical that idea was in the seventeenth century, especially the education of all women, and of the natives of America and Africa.

Second, Comenius proposed that books be compiled that would contain all the information anyone could need; “the condensed essence of all knowledge” must be given to everyone. Three books would be written collaboratively. Pansophia “All Wisdom” would reveal the metaphysics of the structure of soul and world as designed by deity. Panhistoria “All History” would show how all this unfolds in the specific arts and sciences, in all crafts, and other aspects of life. Pandogmatica “All Dogma” the collection of theories about human life and activity and whether they proved to be true or false.

Third a universal language must be collaboratively created. And finally from all the nations across the globe the best minds must collaborate for the betterment of the world, their organization to be known as the College of Light, where a new generation of innovators would be educated. While none of these suggestions were ever realized they did inspire cooperation, and faith in science.

Ironically all of this rational thinking was based on the idea that the end of the world was near. These great intellects of their day were haunted by the fear of imminent doom, though they had no nuclear weapons, no climate crisis. But they also believed that just before the end times there would be great quickening of knowledge. The descendants of Adam would regain the lost language of Paradise just before Jesus returned. Everything would be known and everything understood, by everyone. They hoped by contributing to the process they were bringing the world closer to the Second Coming.

Winthrop left England for Hamburg, the Hague and Amsterdam, meeting not only with potential investors in the ironworks, but with alchemists and philosophers. He was also collecting books and manuscripts. The first of his many attempts to desalinate seawater was already in operation, but back then the salt making was more important than the fresh water left behind. By the fall of 1644 he had the ironworks up and running and was ready to move on to a new venture: mining silver.

By 1646 Winthrop was working on the beginnings of what would become New London. He bought seeds from colonial farmers who had shown luck growing English grasses in America. He ordered trees for his orchard, winter wheat, indigo seeds, and livestock. And most importantly, Winthrop was recruiting geniuses for his colonial college of light.

THE ALCHEMISTS VS. THE MOHEGANS

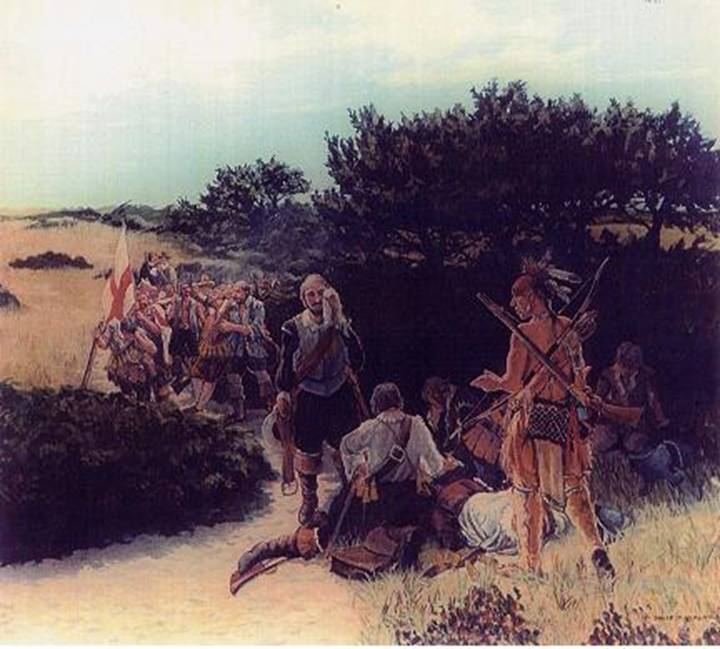

W.C. Wyeth’s depiction of Uncas

W.C. Wyeth’s depiction of Uncas

If you’re familiar with Uncas the romantic Mohegan lead in the feature film Last of the Mohicans you might be surprised to learn there really was a Mohegan chief named Uncas. But he wasn’t at all like the Uncas in the movie.

Winthrop had his eye on a mountain on Connecticut’s frontier where he had found black lead ore. He took the ore with him to England where he got conflicting reports. Important experts declared he had found a silver mine. One dissenting expert insisted he had found no more than graphite. But graphite was rare enough to be a worthwhile commercial venture. The problem with the site was not only that it was outside the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but also that it was deep in native territory where in 1637 the Pequot War broke out. The powerful Mohegan tribe led by their great war chief Uncas, along with their native allies, had joined forces with the English of Connecticut and Massachusetts colonies to crush the once powerful Pequots who had been weakened by deadly diseases caught from the Europeans. The already dwindling tribe was nearly massacred. Bounties were paid by the English for Pequot heads and hands. The English and the allied tribes divided women and children up. The surviving warriors disappeared into the bands of relatives, sometimes in enemy tribes. Five hundred Pequots huddled in a settlement were all that was left of the tribe. The commissioners of the United Colonies, two representatives each from the four colonies, ordered that all legal rights and even the name of the Pequot tribe be erased. The five hundred survivors were now to pay tribute to Uncas and obey him in all things.

The Winthrop house received their fair share of the spoils of war. A young Pequot woman was added to their household as a servant. But there had been a mistake. Uncas already had plans for the girl. He wanted to add her to his growing collection of wives. Uncas chose a new chief from the surviving Pequots, an until-then unremarkable man with the mellifluous name Robin Cassacinamon. Since at the order of the Commissioners of the United Colonies all surviving leaders of the Pequot had been executed by the Mohegans, being named a chief must have been a frightening development for Robin. To make matters worse Uncas ordered him to try to trade with John Winthrop Sr. for the Pequot girl, and if the trade was refused, to volunteer to stay on in service of the Winthrops until he could arrange her escape. Which was more dangerous, to succeed at the task he was given, or to fail?

Either the girl was an indispensable servant or she didn’t want to marry Uncas because his generous trade for her was refused by John Sr. So Robin did as he was told and arranged for her escape. Uncas rewarded him with the treasure John Sr. refused. The Winthrops could not have been pleased, but fortunately for him, Robin had become friendly with John Jr. The two men found mutual respect and shared goals. Robin told John Jr. about the inner workings of tribal politics. John supported Robin’s goal, the survival of the Pequot tribe and its liberation from the tender mercies of Uncas. Robin returned to his five hundred survivors, and Winthrop decided to establish New London, his alchemical plantation right next to the village of survivors. He would plead their cause to the English and natives alike.

The natives thought Winthrop an English chief, since they considered his father chief of Boston. Also because his wife and sister in law lived with him along with several wives of colonial dignitaries who had taken ill and were seeking healing, the natives thought Winthrop had many wives, among them a privilege enjoyed only by chiefs. But watching the smoke rising from his laboratory, the sacred smoke that natives believed connected the worlds of spirit and man, or running long distances carrying messages on behalf of English families begging Winthrop’s help to fight disease, or experiencing the healing power of his alchemical recipes for themselves, the natives began to appreciate Winthrop as a shaman. In their culture to be both chief and shaman was to be a great person indeed.

His old friend Howes not only gave Winthrop good advice about dealing with the natives respectfully; he also sent Winthrop some vocabularies of native language that were probably the work of Thomas Harriot. Winthrop treated the tribes with not only tolerance but with respect for their traditions. When he bought land from them he not only satisfied all requirements of colonial and English law, he also added to the contract a description of the ritual enacted and gave the names of the natives involved. In Winthrop’s village natives and Europeans were living together with mutual concern and a sense of community.

When thirty of his warriors were wounded Uncas was surprised by the arrival of Winthrop who treated them effectively. Soon after Roger Williams leader of the Rhode Island colony wrote Winthrop asking for some of his medicinal powder for his sick daughter. At first Uncas was thrilled to have such a good doctor nearby so he gave Winthrop gifts and participated with the other tribes of New England in the establishment of boundaries for the plantation. This must have been an extraordinary time for Winthrop. Inspired by Rosicrucian ambitions he had gone to the heart of conflict in New England, protected the innocent, and reconciled all tribal factions. In the community he founded natives and English worked and lived together peacefully. The gospel was taught by example, not by force. Pythagorean harmony and hermetic peace seemed emanate all around him as the colonial leaders and charter members of the Royal Society anxiously awaited news about what he was up to next. It must have seemed possible that Comenius was right, and here in America was the first appearance of the society of the Universal Reformation.

Problems began when Winthrop made it clear that the Pequots were now part of his plantation, and were no longer subject to Uncas. Uncas didn’t take kindly to that faux pas. He showed up suddenly with a large force and attacked the Pequots. Bones were broken, cuts were slashed, and men and women, old and young were stripped naked and thrown into the cold river of September in Connecticut. The English weren’t harmed, but their doors were forced open, and their native friends who had hoped to hide with them were dragged away. The message was clear. Uncas wanted his five hundred tribute payers back and he wanted Winthrop and the other English to go back home and leave their plantation to the ants and weeds.

Winthrop already had a questionable reputation among colonial leaders thanks to his business partner Robert Childe’s imprisonment for challenging the Puritan authorities. So Winthrop sent a friend to carry a petition on behalf of the people of his settlement to the United Colonies. But the leaders of Connecticut colony weren’t too pleased with Winthrop. Seems he never asked permission to place his alchemical plantation on what they considered their land. Also, he had violated the property rights, human capital and land, of their proven and loyal ally Uncas. The United Colonies sided with Connecticut. Uncas apologized for getting a little too close to the English during the excitement of the event. Winthrop was ordered to return the Pequots to the Mohegans. But Winthrop was able to postpone the inevitable for many months just by ignoring the order.

In July 1647 Winthrop represented the Pequots at the meeting of the United Colonies. He petitioned for their release from Uncas, and for the restoration of their name and status as a legal tribe. He presented a long list of Mohegan bullying that included extortion, intimidation, cutting fishing nets, stealing food, even murdering innocent natives for the fun of it. The Mohegans also refused to honor their gambling debts. So when asked to gamble by a Mohegan you were really being singled out for anything from extortion to murder. The 500 surviving Pequots, who had seen their families and friends slaughtered, who were trying to embrace the new culture Winthrop was promising, were caught between two worlds.

Again, the commission sided with Uncas. Uncas would pay a fine for the bad behavior of his warriors, a fine he could easily extort from the Pequots when he regained custody of them. He kept the pressure on Winthrop and the Pequots. His brother attacked the Nipmuck tribe who had sold the land for the lead mine to Winthrop; they wrecked a canoe at the plantation’s fishing outpost, and gathered outside the community in a threatening mass before returning to their villages.

Offended by Winthrop’s disobedience, in September 1648 the commission sent armed Englishmen with Uncas and his Mohegan warriors to the plantation. The leader of the English observers made a formal declaration and then the Mohegans were set free to rampage through the town dragging Pequots back into captivity. But the Pequots refused to stay with Uncas. One or a few at a time, they returned to the plantation, until in January 1649 Uncas returned with the English observers and his warriors. The Pequots were beaten and cut, their copper pots, furs, and hemp baskets were destroyed or taken, their shelters knocked down, their clothes ripped off their bodies, old and young alike, and their food supply stolen. The plantation constable’s protests were ignored. They were left shivering and bleeding in the snow. Watching fellow Englishmen stand guard over such cruelty was shocking. As news of the event spread across the colonies public opinion turned against Uncas and the commission.

Three months later March 1649 John Winthrop Sr. was gravely ill. He wrote a letter to his son. He thought the commission was wrong, but he wished the constable hadn’t tried to interfere. He urged his son to obey the commission. He was worried about his son out there with a recently hostile tribe in the wilderness, disobeying the orders of the commissioners. John Sr. had often warned John Jr. of the dangers of too much knowledge. Now here he was doing his crazy experiments in the middle of a battleground, stirring up every hornet’s nest in site. John Sr.’s last request was that John Jr. give up the Pequots, but he didn’t live to see his son’s clever solution to what had seemed an impossible predicament.

Winthrop found a compromise that everyone could agree to. The Pequot would be given a safe area of their own, belonging neither to the Mohegans or the English. They could walk to work at the plantation, and live free of Uncas and his bullying. With public opinion against them this time the commissioners agreed. Uncas was never able to gain complete control over the Pequots again. In 1653 Winthrop convinced the commission to free the Pequot from Uncas. Winthrop kept advocating for them until he also won the restoration of their tribal name and legal rights.

Why did he fight so hard for the Pequot? Was it a matter of pure expedience as he claimed before the commission when he argued if they were dependent on the English that they would become an invaluable source of intelligence about the activities and intentions of other tribes? Did he fight for the Pequot because of his friendship with Robin Cassacinamon, whom he named governor of the Pequot, and whom he used often in negotiations with other tribes? Was he putting to work his Rosicrucian principles, proving that Comenius was right; that a new age of wisdom was dawning that would unite all races? Or did he simply do what he had to do to make his potential silver mine viable? Perhaps all these were motivations behind his extraordinary protection of the Pequot.

It cost him. He couldn’t find workers willing to mine silver in such a cold and dangerous area. Supporters back in Europe were less enthusiastic when news of the trouble with the Mohegans reached them. Robert Childe went back home to England, and the other alchemists who had promised to join Winthrop’s great experiment changed their minds. But Winthrop kept the plantation going. First he made a business out of raising livestock. Then with numerous blacksmiths joining him he began supplying hatchets and hoes for merchants in Hartford. In May 1649 Massachusetts gave him three thousand acres to build a salt works.

THE ALCHEMICAL DOCTOR OF HALF OF CONNECTICUT

New London was more than Winthrop’s experiment, he was to act as the agent, the reporter, the eyes and ears of the Royal Society of London who, when he was in London, tutored him to prepare him for the job. For his alchemical project Winthrop now looked for homegrown talent to replace the reluctant Europeans. In this way he became the central intelligencer of the American colonies. He encouraged George Starkey and many other students of alchemy he found at Harvard, or visiting from Bermuda, or newly arrived from England.

Robert Childe continued to send him recipes from England, recommendations of people and books, and advice about treating the natives respectfully. Local alchemists sent Winthrop questions, or asked his opinion of recipes or sources, they wrote to thank him for the rare book he sent them. Humphrey Atherton who partnered with Winthrop on a new plantation next door joined Winthrop. Alchemist Gershom Bulkeley became the minister of New London. William White, an alchemist and expert on ironworks who had moved to Bermuda returned to New England to work with Winthrop on his alchemical experiments. New London became New England’s medical center, the place where sick people went to get better. “Wherever he came,” Cotton Mather wrote of Winthrop, “still the diseased flocked about him, as if the healing angel of Bethesda had appeared.” Patients arrived from all over the colonies, and even from Europe. Winthrop received heartbreaking letters from sick people from all over the world who had heard about his great talents from friends and relatives. Their conditions can be identified from the descriptions of their suffering. Winthrop usually referred them to physicians in their area; he had more than enough work locally.

Most of Winthrop’s medicines involved preparations of antimony and nitre. One his own most famous recipes, widely distributed by his sons after his death was called rubila. Rubila was made of four grains of processed antimony, twenty grains of nitre, a dash of salt of tin, and a mysterious ingredient that turned the concoction ruby red. He also prescribed flowers of sulphur, purest gold, blue vitriol, iron burnt alum, oregano, sarsaparilla, raisons, saffron, horseradish, tobacco ointment, nutmeg, mugwort, sage, pearls, ambergris, and the penis of a seahorse, which was used to treat kidney stones. He devised a system of color-coded packets so his medicines could be identified more easily. To distribute them he organized a network of female healers who dispensed his advice, too. Winthrop had learned respect for female healers as a young man in England. His cousin Elizabeth was a skilled surgeon in England who had participated in Winthrop’s early alchemical experiments in the 1620s.

Yet in 1650 Winthrop let it be known he was thinking about closing or moving New London, and perhaps even of returning to England. But he seems to have been bluffing. Perhaps contemplating life without New London made officials more cooperative. When Winthrop asked to have the boundaries of the project expanded they were. By 1653 both a gristmill and a sawmill were operational. In 1657, without running for office, Winthrop was elected governor of Connecticut.

Connecticut was a Puritan colony, part of the new monarchy-free world of Cromwell. But now royalty had been restored. Winthrop’s own father in law had signed the document ordering the beheading of the new king’s royal father. With the least official documentation of all the colonies Connecticut was ripe for a revenge pluck. With a signature Charles II could turn it into a royal colony and replace its government with one of his own selection. In the summer of 1661 Winthrop sailed to England. Within months a new witch-hunt broke out in Connecticut. A year of panic began. Eight witchcraft trials were conducted in eight months. By the time Winthrop returned three women and one man had died on the gallows. Five had fled Connecticut.

This was, after all a culture where newlywed couples whose babies arrived prematurely were punished for premarital intercourse with lashes from a whip if they couldn’t afford the fine. So intense was the repression of anger, so stifling the community interest, that for example a young Puritan mother, despairing of ever being worthy of being fit for spiritual grace, spurning the constant “comfort” offered by her betters, threw her newborn down a well and announced that at least “now she was sure she would be damned, for she had drowned her child,” as Governor Winthrop of Massachusetts Bay Colony wrote in his journal. Puritan culture was not peaceful and joyful, anxiety and doubt were considered more appropriate for the almost certainly damned. For these Calvinists the relationship with deity was very conditional and humans were hardly ever able to meet the conditions. As schoolmaster and American Puritan minister Thomas Shepard wrote in his journal: “The greatest part of a Christian’s grace lies in mourning for the want of it.”

When the new charter received the great seal in 1662 Connecticut now included New Haven colony and much of the territory that had been claimed by Rhode Island. The same year Winthrop became a member of the Royal Society. The Royal Society today is a purely scientific organization but in those early years the writings of Hermes and the Neoplatonists, as well as the alchemists and Rosicrucians, were part of the intellectual climate. While in England Winthrop was asked to give many presentations about New England flora and fauna.

Winthrop used his new power to release a woman sentenced to die on the gallows after repeated prosecutions. In another case, a cunning woman skilled at healing was accused of witchcraft including spectral apparitions of herself with a ghostly black dog, and apparently she was psychic since many witnesses testified her predictions came true. She was a student of the astrology books of William Lilly, which she had publicly boasted. Her accusers seemed more malicious. They maimed her animals and vandalized her property. The court ignored Winthrop’s appeal on her behalf and convicted her.

George Bulkeley the young star in Winthrop’s stable handled the next step. He argued that the rule that two witnesses were necessary to convict meant that two people must have seen the same event at the same time. That weakened the case considerably. As for her spectral apparitions, how could the court know if they were not simply the work of the devil, and not of the alleged witch at all? As for her interest in astrology, Bulkeley reminded the magistrates that their own favorite doctors including the esteemed Winthrop, and William Lilly himself, used the art for healing. As for divination it could only be diabolical if the information provided could come from no natural source. To read the stars intelligently and make informed prediction was simply knowledge of nature, like the farmer’s ability to predict the seasons, based on natural cycles, not magic. Soon after Winthrop released the convicted witch and gave her safe passage out of the colony.

Greater Connecticut didn’t last long. One year later Charles II granted his brother the Duke of York a huge grant of land that included New Haven colony and half of Connecticut. The Dutch were to be kicked off Manhattan, as well. And English warships bearing English soldiers were there to enforce the new order. Not only did Winthrop lose his land grant, many of his powerful allies back home lost their positions to loyal royalists. Winthrop formally renounced all claim to Long Island and other territories that had belonged to Connecticut in a public ceremony attended by the agent of the crown. Then he traveled to New Amsterdam to help negotiate the Dutch surrender. New Amsterdam became New York.

Sir Robert Moray was the privy counselor behind this new colonial government, and he too was an alchemist. Winthrop was pleasantly surprised to find that more land than he expected would be under his jurisdiction. But the King was maneuvering slowly but surely toward new charters. First he would get a thorough reckoning of the situation and resources in the American colonies. Then he would establish his own governors. The people would no longer elect them. Winthrop kept as much power as he could by finding good reasons why he couldn’t comply with certain orders.

In May 1675 Charles ordered Connecticut was to surrender all control to the crown. A new government would be appointed. And redcoats were in the harbor ready to enforce the command. As Winthrop lay dying in early April the next year New England was in flames as King Philip’s War threatened to wipe out the colonies. “The blaze of towns was up like torches light, to guide him to his grave,” eulogized a Boston poet. 44 years after the cannon and muskets had saluted his arrival they marked his departure. Winthrop spent his last days working on plans for the rebuilding of New England and the restoration of old alliances. The genteel world of his alchemical plantation New London was disappearing and a new world was being born that would result almost exactly one hundred years later in the establishment of the United States of America, around the time Gosuinus Erkelens bought a mountain near East Haddam, Connecticut known to the locals as “Governor’s Ring.” The president of Yale College at the time, the reverend Ezra Stiles explained it was: “the Place to which Gov. Winthrop of New London used to resort with his Servant; and after spending three Weeks in the Woods of this Mountain in roasting ores and assaying Metals and casting gold Rings, he used to return home to New London with plenty of Gold. Hence this is called the Governor WInthrop’s Ring to this Day.”

WINTHROP’S FLOCK OF ALCHEMISTS

Walter Woodward suggested for Winthrop and his friends the short hand term “The Christian Alchemists.” As he points out, not all were Christian, and the ones who were belonged to various denominations; a Catholic alchemist was included among them.

Walter Woodward suggested for Winthrop and his friends the short hand term “The Christian Alchemists.” As he points out, not all were Christian, and the ones who were belonged to various denominations; a Catholic alchemist was included among them.

The alchemist of Winthrop’s flock born into the least social status was Gershom Bulkeley, who became the son in law of Charles Chauncy, alchemist and president of Harvard College. Gershom was born in Massachusetts in 1636; he worked as a pastor and a minister. At a time in life when his peers would have been unwilling to embark on a new career, Gershom followed his love of Paracelsian medicine into practice as a physician. His healing skills were so in demand he stepped down from his popular pulpit to pursue medicine full time. Bulkeley put together a large library of alchemical works with books by Parcelsus and Sendivogious, including many he hand copied. Not only did Bulkeley’s son become an alchemist, so did his daughter Dorothy.

Bulkeley drew the line at astrology. The influence of the moon and planetary aspects he dismissed in Go With Me a book he wrote for his eleven year old grandson who was considering a future as a doctor. Bulkeley scoffs at a rival physician’s thirty-day prognosis astrological chart, pointing out that it doesn’t even take into account differences in the lengths of months. Yet he speculates about certain astral influences more subtle and sublime. Advice about laboratory work is abundant, including the crucial importance of clearly labeling dangerous chemicals and keeping them away from children. He left his library to his grandson, who grew up to be an alchemist physician and minister himself.

Slatterstrom in his History of Science thesis Alchemy and Alchemical Knowledge in Seventeenth-Century New England gives us a detailed glimpse of the practice of a skilled 17th century American alchemist. Not one of the elite, but a sincere doctor serving a humble community. In Go With Me, Bulkeley “spells out his chemical recipes – and they are truly voluminous. First, he discusses the preparation of substances such as acids, which play an important role in subsequent recipes. For example, he provides a recipe for aqua fortis, saying that it dissolves all metals but gold and tin, as well as a recipe for aqua regis, which he says dissolves gold and antimony. Herbs and other nonchemical substances do not appear for almost 100 pages, and even then only in the context of chemical preparations, ordered by recipe type – i.e. organized into pills, powders, and so on…Bulkeley consistently shows that he has first-hand knowledge of many of the recipes he relates. For example, of pills made from silver, he states, “I have divers times made these pills according to this prescript of Mr. Boyle, and found them excellent,” but he has “since found another way of making them, I think, much better.” His recipe is typical of those in the book, as it involves the alloying and purifying of metals in an aqueous environment – Bulkeley instructs the young doctor to dissolve silver in aqua fortis and add copper plates; the silver will adhere to the copper. Next, when shaken, the silver will fall to the bottom of the container, and more silver will come out of solution to adhere to the copper. In this manner one may purify silver for the pills.”

The flock also included Winthrop’s investor and partner Robert Childe who was born in England. He’s another of those contradictions we find in Europe and the colonies-an alchemist, wisps of Rosicrucian rumors surrounding him, who appears to also have been a strict Presbyterian. He and Winthrop exchanged many letters containing alchemical information, occult speculation, and lists of books being lent or acquired. For example Childe wrote to Winthrop: “One Vaughn an Ingenuous young man hath written Anthroposophia.” Childe had plans for a vineyard, to be not only a business investment, and an experiment in improving the techniques of agriculture, but also for England’s pride, since France should not be the only nation to enjoy such praise for wine making.

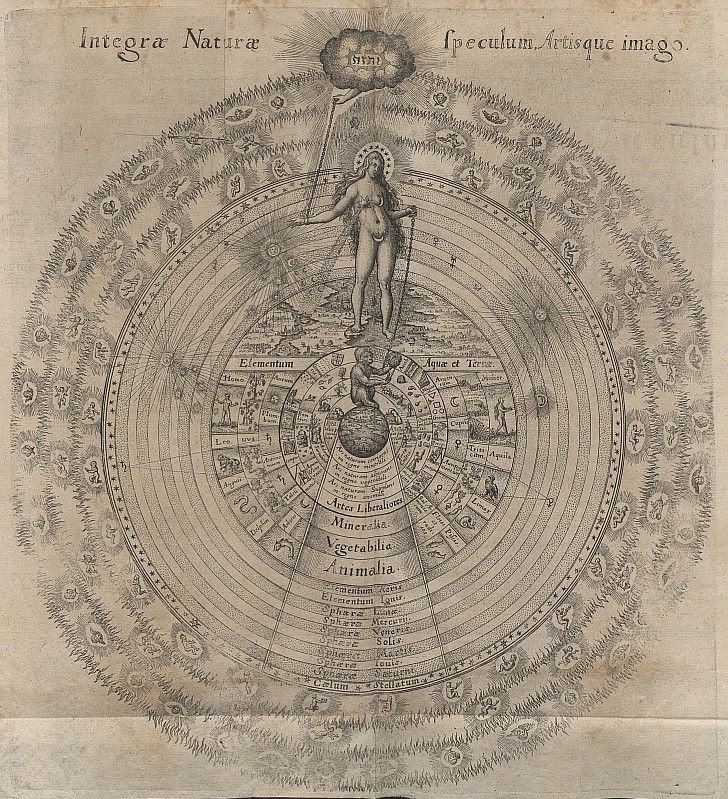

Illustration from a book by Robert Fludd, Winthrop owned eleven copies of the rare volumes Fludd published, probably acquired for him by Robert Childe.

Illustration from a book by Robert Fludd, Winthrop owned eleven copies of the rare volumes Fludd published, probably acquired for him by Robert Childe.

Elias Ashmole was the great antiquarian of his age. In his diary Ashmole relates tantalizing glimpses of his meetings and correspondences with Rosicrucian apologists, and alchemists, as well as cabalists, astrologers, members of the inner circle of Francis Bacon, fellows of the Royal Society, and early freemasons. Most of John Dee’s library, including his manuscripts, was in Ashmole’s collection. In his Theatricum Chemicum Britannicum (1652) Ashmole in his prologue declared that the Earl of Norfolk had been cured of leprosy by a brother R.C., and Queen Elizabeth had been twice saved from smallpox by another. He was a saint to astrologers, protecting them from Cromwell. It’s extraordinary that he had influence over both Cromwell and King Charles II, who considered Ashmole a favorite. Kittredge writes: “We have still further traces of Childe in 1651. On March 7, Elias Ashmole makes the following entry in his Diary: “I went to Maidstone with Dr. Child the physician,” placing Childe near the heart of England’s alchemical community.

But perhaps the most dramatic evidence for Childe’s interest in the esoteric far beyond the pale of your average Presbyterian is the dedication in the 1651 English translation of the Three Books of Occult Philosophy by Agrippa:

“To my most honorable, and no less learned Friend, Robert Childe, Doctor of Physick.

SIR! Great men decline, mighty men may fall, but an honest Philosopher keeps his Station forever. To your self therefore I crave leave to present, what I know you are able to protect; not with sword, but by reason; & not that only, but what by your acceptance you are able to give a lustre to. I see it is not in vain that you have compassed Sea and Land, for thereby you have made a Proselyte, not of another, but of your self, by being converted from vulgar, and irrational incredulities to the rational embracing of the sublime, Hermeticall, and Theomagicall truths. You are skilled in the one as if Hermes had been your Tutor; have insight in the other, as if Agrippa your Master. Many transmarine Philosophers, which we only read, you have conversed with: many Countries, rarities, and antiquities, which we have only heard of, and admire, you have seen. Nay you have not only heard of, but seen, not in Maps, but in Rome it self the manners of Rome. There you have seen much Ceremony, and little Religion; and in the wilderness of New England, you have seen amongst some, much Religion, and little Ceremony; and amongst others, I mean the Natives thereof, neither Ceremony, nor Religion, but what nature dictates to them. In this there is no small variety, and your observation not little. In your passage thither by Sea, you have seen the wonders of God in the Deep; and by Land, you have seen the astonishing works of God in the unaccessible Mountains. You have left no stone unturned, that the turning thereof might conduce to the discovery of what was Occult, and worthy to be known. It is part of my ambition to let the world know that I honor such as your self, & my learned friend, & your experienced fellow-traveler, Doctor Charlet, who have, like true Philosophers neglected your worldly advantages to become masters of that which hath now rendered you both truly honorable. If I had as many languages as your selves, the rhetorical and pathetical expressions thereof would fail to signify my estimation of, and affections towards you both. Now Sir! as in reference to this my translation, if your judgment shall finde a deficiency therein, let your candor make a supply thereof. Let this Treatise of Occult Philosophy coming as a stranger amongst the English, be patronized by you, remembering that you your self was once a stranger in the Country of its Nativity. This stranger I have dressed in an English garb; but if it be not according to the fashion, and therefore ungrateful to any, let your approbation make it the mode; you know strangers most commonly induce a fashion, especially if any once begin to approve of their habit. Your approbation is that which will stand in need of, and which will render me,

SIR,

Most obligedly yours,

J. F.”

According to James Ferguson, the early go to source for most bibliographical questions related to alchemy and rosicrucianism J.F. was John French (1616-1657) a physician remembered for his advancement of distillation in chemistry. Tobias Churton and others have argued that James Freake was J.F. Churton also argues that Robert Childe was in a secret society with Samuel Hartlib, Thomas Vaughn and Elias Ashmole.

Hartlib was dubbed “hub of the axletree of knowledge.” The transplant to England from Poland was a friend of the great educator Comenius, and of the poet John Milton of “Paradise Lost” fame. He was probably the best-connected intellectual of his day because he exchanged letters with every kind of expert he could find. Hartlib’s friends and correspondents amounted to an Invisible College, which became one of the principle foundations of the Royal Society, though Hartlib himself was excluded from membership. For his contributions to everything from bee keeping to increasing crop yields and collecting medical cures (rational and irrational), Cromwell awarded Hartlib a pension to live on. But when the royals returned, Hartlib found himself abandoned; he died in poverty.

Hartlib spent years discussing a colony of the learned perhaps in Virginia, but none of the interested parties ever committed to such a terrifying journey across the Atlantic and such an uncertain future on the outer edge of a vast unknown continent. When Hartlib met Winthrop he was impressed by this brilliant young alchemist from America bearing samples of the richest mineral ore Hartlib had ever seen. But he was one of those who cooled off when the Mohegans got busy.

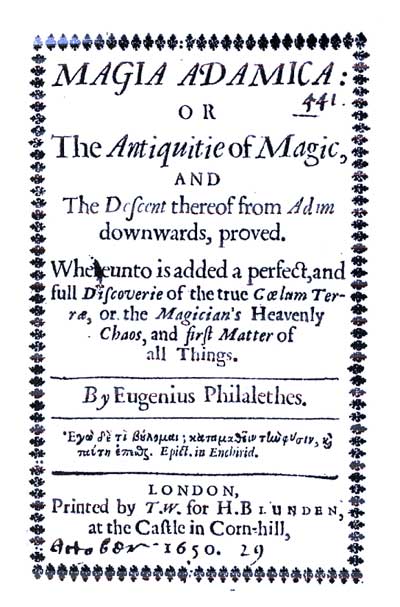

But what of the fourth member of Churton’s alleged Rosicrucian secret society, Thomas Vaughan?

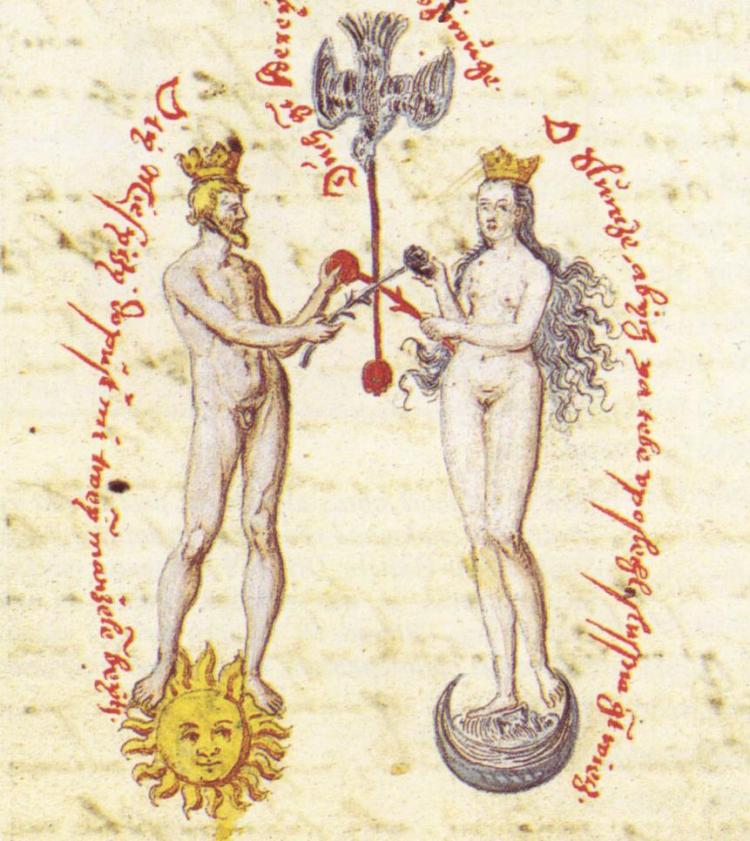

THE ALCHEMICAL MARRIAGE

Thomas Vaughan was involved in a plan by Robert Childe to form an alchemical circle, but Vaughan referred to himself as a member of the Society of Unknown Philosophers. Vaughan, using the pen name Eugenius Philalethes, was the author of Anthroposophia Theomagica, a book that weaves magic and mysticism with quotations about Plotinus, and from the notorious natural philosopher (occultist) Agrippa and the pagan biographer Plutarch and Virgil the pagan poet of ancient Rome, not to mention Hermes Trismegistus and Pythagoras. “I look on this life as the progress of an essence royal: the soul but quits her court to see the country,” Vaughan wrote. He also complained: “It is an age of intellectual slaveries: if they meet anything extraordinary, they prune it commonly with distinctions or daub it with false glosses, till it looks like the traditions of Aristotle. His followers are so confident of his principles they seek not to understand what others speak but to make others speak what they understand. It is in Nature as it is in religion: we are still hammering old elements but seek not the America that lies beyond them.”

Vaughan was the twin brother of Henry Vaughan, the physician and metaphysical poet who influenced everyone from poets like Wordsworth and Tennyson to that prophetic master of science fiction Philip K. Dick. Thomas started out as a minister in his native Wales, with a generous salary including house and lands far above the average expectation for a young man. John Walker wrote about Vaughn’s case in Sufferings of the Clergy (1714), reporting he was removed from his parish “for Drunkenness, Swearing, Incontinency, being no Preacher, and what was in their Opinion worse than All, for having been in Arms for the King: And perhaps the last Article was the only Proof and Evidence of all the Rest.” But Vaughan admitted later in his writing that he “revelled away many years in drinking.” The Civil War did far worse than remove preachers from their parishes. Death and mutilation were common to both sides. Vaughan retreated to his experiments and studies at Oxford.

A tragic love story is at the core of Thomas Vaughan’s life. He worked closely in his alchemical and mystical experiments with his wife Rebecca, his sorer, or sister in the great work. Rebecca was no mere assistant. All the breakthroughs he achieved were either done with her help or by her inspiration. His work after her death merely played out what he had already learned. Her skill was so great he named one of their discoveries Aqua Rebecca, because without her help he couldn’t reproduce it.

But in 1658 Rebecca had nightmares about being attacked by a stallion then she sickened. By April, as she lay dying, Vaughan obsessively chased after a formula he had forgotten from his early days working with her. Perhaps he thought it would cure her, though he nowhere mentions this. Instead, when he exults at achieving his goal just as she died the hollowness of his triumph echoes in the notes he jotted down, first published by A.E. Waite about two hundred years later. Vaughan at first declares that the grief of so great an impending loss was fuel for his efforts, and that he had been graced with success as a compensation for the loss of his beloved, but over time he shared the depth of his sorrow and the tragedy of denial he felt keenly. He had allowed abstraction to draw him into an escapist grand effort, and he missed the real moment of transformation, a moment that haunted him the rest of his melancholy life. His notes end with bereft confessions of his yearning for her, his regrets, and a detailed, heartbreakingly fond list of every possession of hers still remaining to him.

The notebook record of their work together he now flipped over and gave a new title page. He invented a monogram out of the initials of her first name, his, and their last name: T R V; he used it to sign most of the entries, even the ones made after her death. Just before the first anniversary of her death, Thomas dreamed of Rebecca. She appeared covered in “thin loose silks” of unearthly green; she was taller and her face was shining with an angelic glow. Just before meeting Rebecca in 1651, Tom had written Lumen de Lumine, or a New Magical Light, in which he described a goddess of wisdom dressed in green who finally enlightens him. Tom took Rebecca’s appearance in the green dress in his dream as a clear message. She had been Beatrice to his Dante, and she would continue to be.

In the months following her death he had dreams about her that brought him premonitions, for example she appeared in a dream to correctly predict his father’s death in June that same year. Haunted by so much death Tom began having nightmares about the attacking stallion. He was certain his end was near. But at the end of August he had a dream about his wife that left him feeling he now understood what the bible meant by having a home in eternity.

1888 edition edited by A.E. Waite

1888 edition edited by A.E. Waite

The melancholy Vaughan then followed the court as an alchemist supported by the king, thanks to his friend, fellow royalist, and partner in alchemical experimentation Sir Robert Moray, whose accomplishments included being a judge, mathematician, statesman, soldier, diplomat, spy and the first president of the Royal Society. Along with Ashmole, Moray is one of the two earliest recorded freemasons in English history. Moray, probably assisted by Vaughn, helped Charles ll with his own alchemical experiments. When the royal court left London for Oxford to escape the plague in 1665 Vaughan was included.

In 1652 Vaughan had translated and published the Fama Fraternitatis Rosae Crucis, the bedrock document of the Rosicrucian movement, the first English edition since it’s original appearance in Germany forty years earlier in 1614. Scholars have argued that Moray gave Vaughan a Scottish manuscript version of the Fama that had belonged to Moray’s father. This has led to speculation that Moray was a Rosicrucian. But what does that mean exactly? That he was a member of a secret society of almost superhuman adepts? That he was one of the original participants in the benevolent conspiracy of a secret order of Masons? What if he were merely inspired by the Rosicrucian writings? He doesn’t mention Rosicrucians anywhere in his letters, but of course a Rosicrucian wouldn’t.

In 1664 John Winthrop Jr. wrote to Moray about his discovery of a faint star near the planet Jupiter that he thought might be the fifth moon. Modern astronomers hesitate to credit Winthrop with such a feat of visual acuity but the evidence in the letter is undeniable. Moray was said to have had second sight, said to be common among highlanders; he foresaw his wife’s death, but not the death of his friend Vaughan. In 1666 one of their experiments led to Vaughan inhaling mercury fumes, killing him. Moray paid for his friend’s funeral.

Moray lived another seven years; near the end of his life he became a recluse, living like a very poor person, obsessively pursuing alchemical experiments in a dirty laboratory. For all we know he was having the time of his life unfettered by court and other responsibilities, or perhaps he was a senile almost ghost muttering to his old friend Tom Vaughan. When Moray died the king ordered him buried in Westminster Abbey.

THE ALCHEMIST STARKEY

In the 18th and 19th centuries Robert Childe was thought to be the writer behind the highly esteemed books of Eirenaeus Philalathes, a pseudonym that must have been a tribute to Eugenius Philalathes. Some historians have speculated that John Winthrop Jr. might have been the real Eirenaeus Philalethes. An obscure bit of evidence for Winthrop as Eirenaeus first appeared in Ferguson’s Bibliothecha Chemica where the usually dependable bibliophile says they are one and the same. In the Bacstrom Manuscripts in the Manly P. Hall collection in vol. 12 in his notes to the anonymous manuscript Some Curious Processes, and in his notes to his hand written copy of Lambsprink’s The Great Work, sea captain alchemist Bacstrom wrote that Dr. Winthrop was Eirenaeus. Most likely Bacstrom was reporting an oral tradition, which of course doesn’t necessarily make the identification true, but it is an intriguing detail.

So will the real Eireneaus Philalathes please stand up, please stand up? The likeliest candidate is George Starkey. As Newman shows in his essay in the Alchemy Revisited striking similarities of source and expression can be found between letters sent from Starkey to Boyle and an alchemical work attributed to Eireneaus.

George Stirk as Starkey was originally known, was born in Bermuda but educated at Harvard, where alchemy was all the rage. He settled down in Boston where he practiced Paracelsian medicine professionally. His experiments with the technology of alchemy as it was becoming chemistry were serious enough that he left America for London in search of better materials for building his alchemical ovens. He had just gotten married, and changed his name to Starkey. Recently historians have argued that Starkey is America’s “earliest important scientist.”

Starkey’s skills made him popular in Samuel Hartlib’s circle of reformers and Paracelsian doctors and alchemists. He was known for being able to produce greater quantities of quality aromatic oils thanks to his secret process. His most famous demonstration or claim to the elixir was the rejuvenation of a withered peach tree. But his influence goes further than that.

William Newman, professor of history of science at Indiana University, argues that Starkey was probably the most widely read American scientist before Ben Franklin. Starkey’s work is said to have been an influence on three of the most influential intellectuals of the age: Isaac Newton, famous philosopher and physician John Locke, and mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz. Robert Boyle, a pioneer of scientific method and one of those most responsible for bringing the butterfly of chemistry out of its alchemy cocoon, was impressed when Starkey cured his until then incurable illness. Starkey became Boyle’s chemistry tutor. Boyle quotes Eirenaeus Philalathes admiringly in his own works. But he does not appear to have known that Starkey was the author of the Eirenaeus Philalathes books. In fact, critics of the day complained that such a profound author should be distributed by Starkey, a difficult and unpleasant fellow. Recent studies of Starkey’s notebooks reveal method and clarity closer to chemistry than alchemy.

Eirenaeus Philalathes wrote elevated prose inspiring to spiritual and political reformers alike, of course at the time if you were one you were likely to be the other. Eireaneus wrote in alchemical code, a language of metaphors, the uninitiated reader is left to wonder how to procure such ingredients as “the doves of Diana,” “the menstrual blood of our whore,” “Gehennical Fire” (hell fire in current lingo) and “a Fiery Dragon.” While possibly easier to obtain, the exact use or meaning of “a hermaphrodite,” “a mad dog” and “a chameleon” remain obscure. Gehennical Fire is apparently a universal solvent, but how to store something that dissolves anything it comes into contact with, literally disassembling the building blocks of our material world? And how exactly does the amalgam “fly away seven times”?

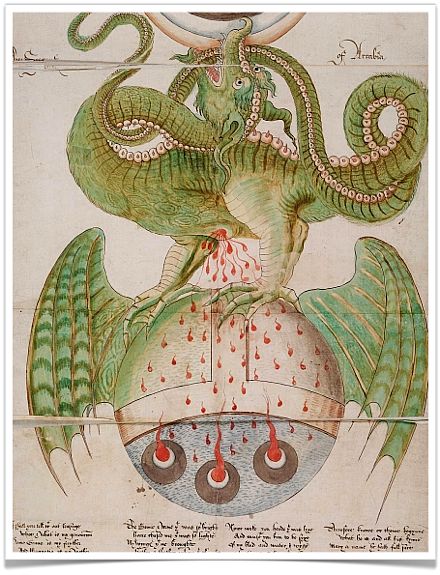

Starkey presented himself as the editor and distributor of the secretive Eirenaeus. From 1654 to 1683 over a dozen works were published, including The Marrow of Alchemy, Secrets Revealed andThe Secret of the Immortal Liquor called Alkahest. Six of his works have titles that include the illustrious alchemical name of Sir George Ripley. After twenty years of study in Italy where he was a favorite of Pope Innocent VIII he went home to Great Britain in 1477 where he wrote The Compound of Alchymy; or, the Twelve Gates leading to the Discovery of the Philosopher’s Stone. The book was dedicated to King Edward IV and was a favorite of his. Ripley was one of the first to compose poetry on alchemy and his magnificent scroll and many writings made him famous. His wealth was legendary and made it seem more plausible that he could turn lead to gold

There are only 23 copies of the Ripley Scroll in existence. According to London’s Science Museum “The scrolls are believed to be 18th Century copies and variations of a lost, 15th Century original.” I was fortunate as a kid to have perused the one in the collection of Manly P. Hall with the great collector himself.

A section of a Ripley’s Scroll

Ripley also has the distinction of being perhaps the first to publish previously unknown manuscripts by the great Raymond Lull, who two hundred years earlier had written groundbreaking works on not only mathematics, statistics, classification, and architecture, but also mysticism and the occult.

Starkey seems to have enjoyed making up details about the life of Eirenaeus. One might wonder about multiple personality disorder until the predicament Starkey was in becomes clear. Starkey in his letters to Boyle writes that he had received offers to use his secrets that could have made him very wealthy. Investors were eager for him to attempt gold and silver making on an industrial scale. But Starkey said that such a life would be like hard labor to him, removing him from what he loved most, studying nature and learning its secrets. Starkey shared his secrets with Boyle, only upon assurance that Boyle would never sell them. The illuminations Starkey had received by grace of what he called The Father of Lights were not for mere vulgar profit. They were to contribute to the reform of the world, the restoration of paradise by divine revelation. It was a delicate situation. Starkey needed Boyle’s financial support so he had to show his efforts worthwhile, but if he gave up too many of his trade secrets he wouldn’t be useful anymore.

Starkey attributed part of his genius to dreams. One of these dreams was a major contribution to the myth of the adept or initiate who appears to the sincere alchemist. In a letter to Boyle, Starkey writes: “”Behold! I seemed intent on my work, and a man appeared, entering the laboratory, at whose arrival I was stupefied. But he greeted me and said: “May God support your labours.” When I heard this, realizing that he had mentioned God, I asked who he was, and he responded that was he my Eugenius; I asked whether there were such creatures. He responded that there were…Finally I asked him what the alkahest of Paracelsus and Helmont was, and he responded that they used salt, sulphur, and an alkalized body, and though this response was more obscure than Paracelsus himself, yet with the response an ineffable light entered my mind, so that I fully understood. Marveling at this, I said to him, “Behold! Your words are veiled, as it were by fog, and yet they are fundamentally true.” He said “This is so necessarily, for the things said by one’s Eugenius are all certain, while those just said by me are the truest of all.” Eugenius is Greek, the usual translation is “well born” but “good spirit” or “great spirit,” even guardian angel or higher self might be closer to the meaning Starkey intended.