Part 1: Hiram K. Jones the Western Wonder

On Sunset Boulevard, across the street just east of the Whisky a Go Go, is a store named Hippocampus where since it opened in 1967 people have found oddities, curiosities and treasures. Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, or Janis Joplin probably wandered in when it was new. By the time I was fortunate enough to find a treasure there, almost three decades later, the woman who had always run the place had become frail. She stayed home but she was always a phone call away and any important decisions were still hers to make. On a chilly autumn night my girlfriend and I wandered in to find in the small display area upstairs a big leather bound book. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw the title on the spine: The Platonist.

The Platonist was a newsprint magazine published in the Midwest in late 19th century America. I turned the thin fragile pages revealing many rare translations by the great rogue scholar Thomas Taylor, a scattering of occult classics, and an announcement about plans for a colony where devoted philosophers could study the religions of the world. Print on demand and online archives have made the contents easily available to anyone, but then, when the Internet was young, The Platonist was famously rare. The pages were brown with age but otherwise in excellent condition for a publication almost 110 years old. I showed the book to my equally thrilled and reverent girlfriend. To find such an esoteric rarity there on Sunset Boulevard seemed an impossible serendipity.

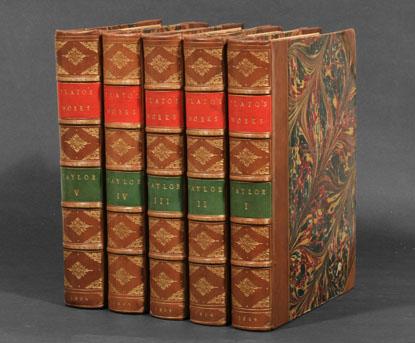

We didn’t have much money and didn’t think we could afford such a treasure. But I knew there was the chance that they didn’t really know what it was. You couldn’t yet click over to Amazon or Abebooks and find the going price. I also knew that sometimes books like this were sold cheaply because their owners wanted them in the hands of people who would appreciate them. So I picked up the book, along with a couple of old Thomas Taylor editions I found nearby, and with trepidation approached the rather severe gay man behind the counter.

I asked him how much the books cost. He had no idea so he called the owner. We watched him talk to her on the phone in the back of the store. He put the phone down and walked over to ask me if I wanted the books because of their decorative leather bindings. I told him we wanted to read them. The telephone conversation ended quickly. He told us we could buy The Platonist for $75, all three books for $125.

Back home we pored over the pages stuffed with Neoplatonic commentaries, wisdom quotes and inspiring facts, nearly forgotten history in dense double columns; essays and translations of rare works by men I hadn’t heard of before: Thomas Johnson, Hiram K. Jones, Aldexander Wilder. A marvelous compendium of profound and inspiring thought, yes, but what fascinated us most about The Platonist was that it provided proof that in the heart of the old west, in the last days of Billy the Kid and Jesse James, around the time of the infamous gunfight at the O.K. Corral, some Americans were studying Plato. Little did we know how popular Plato really was in those days.

THE OTHER PLATO

Plato threatens Aristotle with a wet willy.

For most Americans, Plato is a misspelling of Pluto. For most of us who heard about Plato in one classroom or another, who were perhaps forced to read a dialog, the name conjures memories of dreary word games and rhetorical calisthenics requiring attention spans now extinct. Yet Plato through his school and his later successors the Neoplatonists leads directly to the natural magic of the ceremonial magicians of the middle ages, and to the cultural liberation we call the Renaissance. Scratch the surface of the metaphysics of William Blake, Percy Shelley, or for that matter Shakespeare and you’ll find Plato. In the late 1960s New York City’s notorious swinger sex club, a popular symbol of the sexual revolution, was called Plato’s Retreat. Plato could be called the founding father of the New Age movement of the late 20th century, since his writings are the definitive pagan influence on western belief in reincarnation, astrological influence, alchemy and sacred geometry.

Yet there is something different about these teachers and housewives who formed Plato clubs and met in parlors to discuss ancient Greek philosophy. They were pioneers, children and grandchildren of pioneers, who had built not just a town but hospitals and schools. Upper class to be sure, but the sturdy base of American stock, not the children of great families, or university legacies, there’s something 1950s suburban about their earnest desire to use new found free time well. An elite? Well, perhaps they were trying to develop into one. At its peak the Plato Club of Jacksonville, Illinois had over four hundred members, but many were spread across the American continent and even overseas so the largest group at a popular event would be about two hundred, in a town whose population even today numbers less than twenty thousand. It’s a pity we don’t have a more careful, and perhaps gossipy record, of this obscure small town renaissance. The formal papers presented by members and reprinted in The Platonist and other philosophical journals give us little sense of the impact of Platonism on these people who were defining American culture at the edge of the frontier.

To them Plato was not just another name for boredom on a history of philosophy reading list. They knew his writings had long been forbidden. Plato was unknown to most Americans, left out of history. They knew the context of Plato’s epic creation. Under their great ruler Pericles the Athenians had been lifted into a cultural and economic empire that led them to a ridiculous in hindsight act of hubris. They made war on Sparta. Sparta wasn’t shy about using Persian supplies to conquer Athens. Athenians who had witnessed the giddy cultural ecstasy of the early days of the Athenian Empire found themselves destitute in the ruins of what had recently been realized dreams. Socrates was one of many scapegoats. His philosophical questioning had turned the minds of some young men; they began to question the war. That was treason. Plato presumably was there when Socrates drank the hemlock and died by order of the Athenians. Plato’s works are more than one kind of masterpiece. Beautiful biographical monuments to the memory of Socrates, the dialogs were also a deeply subversive creation. Plato took the persistent questioning practiced by Socrates to a new level examining key areas of human life from life after death (yes) to the most effective and fair form of government (not democracy).

Thomas Taylor’s complete translation of the works of Plato.

Thomas Taylor’s complete translation of the works of Plato.

The intelligencers of early colonial America had editions of Plato on their bookshelves. Ralph Waldo Emerson read Thomas Taylor’s translations of Plato, Aristotle, and the Neoplatonists as avidly as they had been by Shelley. Shelley translated two of Plato’s dialogues. “Out of Plato,” Emerson wrote, “come all things that are still written and debated among men of thought.”

Emerson who befriended and visited leading Platonists of the Midwest thought of them as the ultimate outpost of what he considered true civilization. The idea of a rough farmer reading Plato by firelight in his simple cabin on the prairie captured Emerson’s imagination. He didn’t realize that like their beloved Neoplatonists, these Midwestern Platonists were at the end of a line that was about to close. America was about to give birth to her own philosophy and psychology: materialism. Embracing industrialism American thinkers banished metaphysics to the ash heap of outgrown nonsense, and Plato with it.

“THE WESTERN WONDER”

How did Plato the great philosopher of pagan antiquity come to be studied on the edge of the prairie? Did freemasons transplant Platonic doctrine from Europe to America? The great romantic poets of Britain were inspired by Platonic translations, did those sparks their poems catch fire across the Atlantic? For the ultimate father of American Platonism we need look no further than Ralph Waldo Emerson. For example, Thomas Moore Johnson, the publisher, editor and principle writer of The Platonist, named his sons Ralph Proclus, Franklin Plotinus, and the whimsical Waldo Plato. Was New England, then, the center of American Platonism? No, that honor belongs to Jacksonville, Illinois, or as it was known the Athens of the West.

No one is sure what made Jacksonville such fertile soil for Platonism. Some writers have argued that the first settlers came from cultured places, like Huntsville, Alabama then known as the Athens of the South, while the founding fathers were all Yale University men, and perhaps brought Platonism with them. But the man at the heart of 19th century Platonism in the American Midwest and beyond was a doctor in Jacksonville, a town then as now known for its hospitals. Hiram K. Jones was a conscientious physician with a successful practice. Hiram had nicknames, none of them having to do with his good doctoring or his service to Illinois College. He earned his nicknames by becoming the most popular Platonist in America. He was “the modern Plato,” the “western metaphysical giant,” and “the western wonder.” He was America’s foremost expert on Plato, according to Emerson himself, though at the Concord School one critic dismissed Jones as a “loose, uncouth thinker,” and readers are left to wonder how a man who never learned to read ancient Greek could become an authority on Plato.

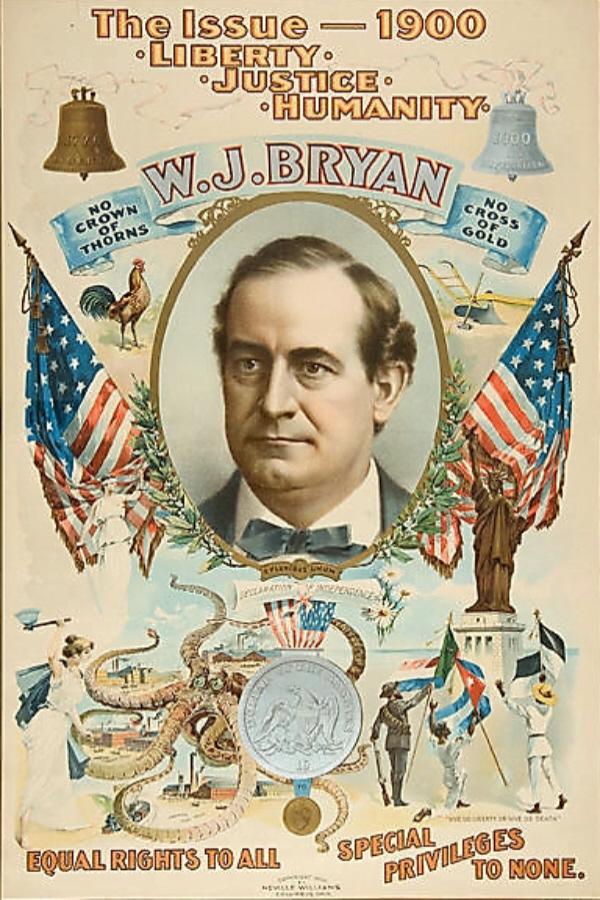

Hiram was born in the summer of 1818. Andrew Jackson was president. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was published that year, and the U.S. Congress created an American flag of thirteen red and white stripes and one star to be added for each state; there were twenty stars at the time. His father’s father, an immigrant from England, had served under the command of George Washington in the Revolutionary Army. Hiram was a Lincoln man. He felt so strongly about abolition he campaigned for office to fight slavery, but he lost. The underground railroad had a stop at his own house. During the Civil War, Hiram provided medical services to union soldiers and their families for free. Not only did he shelter runaway slaves but also starving students, including William Jennings Bryan who later became the presidential candidate for the populist wing of the Democratic party in three elections, though he never won. Some authors have argued that Bryan and his bombastic campaigns were the model for the Wizard of Oz.

Three time populist presidential candidate nominated by some writers as the inspiration for the character of the Wizard of Oz.

Three time populist presidential candidate nominated by some writers as the inspiration for the character of the Wizard of Oz.

Illinois College was the place where Hiram’s passion for metaphysics began. “When I was a student in Illinois College,” he wrote, “there were two other students and myself who got hold of Emerson’s writings. Of course we were ridiculed for dabbling in such transcendental nonsense. These writings were then denounced on all sides. We continued to read Emerson. Now within one short lifetime that thought has conquered and subdued all minds.”

In 1854 Hiram became superintendent of the Jacksonville Hospital for the Insane only until someone else could be found. After that he returned to his practice, generations of loyal patients he served until a month before his death in 1903 almost five decades later. It took him thirty years to put out a shingle with his name on it. When a new patient hunting for his office on a hot day nearly fainted he finally put up a sign.

Hiram wasn’t content with Emerson; he wanted to read the master’s sources, which led him to Thomas Taylor, Plato, and the Neoplatonists. By the early 1860’s Hiram was reading Plato for himself. Any friend who showed mere polite interest would find himself listening to passages of Plato read out loud.

How did Hiram become the preeminent 19th century American Platonist? He was in Jacksonville at just the right time. The prairie was only a short wagon ride away, but for the prosperous elite of Jacksonville free time was an invitation to culture. Two well to do wives and an unmarried well to do woman formed a reading club with the intention of getting away from the daily grind that even rich women couldn’t avoid on the edge of the prairie. They wanted a regular meeting devoted to spiritual and intellectual enrichment. They thought perhaps they’d read the bible but they had heard Hiram K. Jones praise Plato so they asked his opinion. Hiram was always ready to talk about Plato. They all agreed to meet every Saturday morning. That was the humble beginning of the Plato Club in 1866, which influenced American culture for more than thirty years.

Raphael’s fresco of Plato’s Academy.

Raphael’s fresco of Plato’s Academy.

Jacksonville’s Saturday Morning Plato Club quickly attracted local teachers. Mostly female at first, the club soon included the principal of the local high school and other male educators, but women were always in the majority. Dialogs were read out loud and discussed in depth. Jones would then interpret the meaning in passionate rhetoric. His judgment was not to be questioned. The locals considered his opinions worthwhile, and happily accepted the benevolent tyranny of their philosopher king. Hiram’s talks about Plato drew from the literature and religion of the entire world as he sought to illuminate by comparison. From Dante and Shakespeare to parallels in Hindu, Persian, Chinese, and especially Christian thought. After all, Hiran and his wife were upstanding members of the Congressional Church. Hiram entranced his listeners with an exotic concoction of civilizations that must have been comforting out there on what had recently been the frontier.

The Jacksonville Plato Club hosted visiting guest speakers including the illustrious New England Transcendentalist Bronson Alcott, and Thomas Johnson. Membership to the Plato Club was open to any religion, gender or race. Some members merely enjoyed it as a social club, an intellectual amusement, while others had moved to Jacksonville specifically to study philosophy. The membership cards featured an illustration of a butterfly, symbol of the soul, with a saying in Greek: “The soul, aye, the immortal.”

Jones became an in demand lecturer. Soon Plato Clubs sprung up in other towns, but lacking their own Hiram K. Jones these clubs never achieved the vigor of the original, although a story is told of a society lady who tried to one up a new acquaintance by asking her if she had ever looked into Plato, but who was herself one upped instead when the response came: “I’ve been studying Plato in the original Greek for three years.”

Why this attraction for Plato among Midwestern dowagers? Women were claiming power in various ways in American society. Female mediums delivering lectures in trance could command the attention of large halls filled with men around whom they would otherwise have to be silent. Women were organizing to demand property rights and the vote. Victoria Woodhull became the first female broker on Wall Street, and the first woman to run for president. Plato was widely respected as the pinnacle of classical philosophy, for generations the exclusive province of men. Women who developed a command of this difficult subject proved their equality with their most sophisticated male peers. But Plato was also teaching them the arts of argument and rhetoric, and a profound philosophy of life.

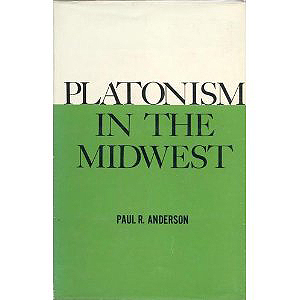

As Paul Andersen, the closest thing we have to a biographer of Hiram K. Jones, wrote in 1963: “It was an amateur movement in the sense that none of these people gave their complete time to philosophy and none of them wished to become so involved in the technical issues of philosophy as to disqualify themselves for participation in the solution of immediate and personal problems.”

As Paul Andersen, the closest thing we have to a biographer of Hiram K. Jones, wrote in 1963: “It was an amateur movement in the sense that none of these people gave their complete time to philosophy and none of them wished to become so involved in the technical issues of philosophy as to disqualify themselves for participation in the solution of immediate and personal problems.”

Anderson described his Americanized Platonism: “Jones regarded philosophy as a necessary orientation for the whole business of human living. It gave impetus to vocational pursuits and it enriched the leisure hours. In short, it brought the tangled miscellany of human experience into some semblance of harmony, providing meaning and purpose for all.”

While devoted study of a pagan genius may not seem like a traditional Christian activity, the members of the Plato Club were not rejecting their churches to embrace ancient Greek religion. Some were however willing to view Christianity as one religion among many, and all of them worth studying. But how extraordinary it must have been for these women consciously creating the culture of their new town on the edge of the frontier in the middle of the still wild continent, the ideas of Plato refining their thoughts.

Nearby Quincy, Illinois was an important partner in the rise of Midwestern Platonism. On Nov. 16, 1866 twelve ladies of Quincy were invited to the home of Mrs. Denman, did any of them think of themselves as a coven of thirteen though they were not witches? Their goals involved feminism, education, and self-improvement through philosophy. A name considered for the club was The Embryonic Free and Independent Anti-Red-Tape Society. A century later that could have been the name of a hippie rock band or a generation later a riot grrrl zine. Instead they settled on Friends in Council.

Mrs. Louise Fuller, who was living for a short time in Quincy, but who was from Jacksonville, and a member of the Hiram K. Jones circle, was probably the first to suggest he address the new group. Their first organized activity was reading important books. They began with The History of the Rise and Influence of Rationalism in Europe by Lecky. In year two with the membership now up to about seventeen began to read the dialogues of Plato, helped along by visits from Jones, some a month long. After the first year enough of them felt frustrated that they traded Plato in for the Stoic philosopher Epictetus. But soon they were back to Plato who occupied every meeting for the next year. Mrs. Fuller, back home in Jacksonville, would become editor of the Journal of the American Akademe. Many members of Friends in Council became members of The Plato Club in Jacksonville, and they joined the Plato Club in Quincy founded by a successful businessman. In 1881, 35 years after Friends in Council began, Mrs. Denman died. The clubs lasted only a little while longer.

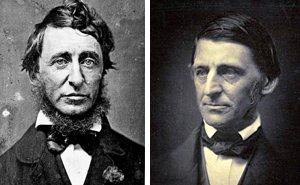

Thoreau and Emerson, Thoreau looks like he just got back from Burning Man.

As his lectures became more popular Hiram became friends with the big three of New England Transcendentalism: Emerson, Alcott, and Thoreau. All were visitors to Jacksonville, and guests in Hiram’s house. In 1879 he helped inspire the self taught traveling teacher Alcott to realize his dream for an adult summer school: the Concord School. Many of the people who paid to attend came from the Midwest. For four years Jones took up the cause of Plato in a debate with America’s leading expert on Hegel and students were spellbound by the clash of ancient Greek and modern German philosophies. Jones was known for five-hour lectures. Hipsters of the time would enjoy an hour, then go out and row on the slow Concord River for an hour, then return to listen to more of the lecture.

Jones thought the Concord School should be moveable and he thought it made sense to move it to the Midwest. But Alcott disagreed. Feeling rejected on behalf of the entire Midwest Jones never lectured at the school again, Plato’s position was abandoned, and Hegel from then on dominated the suddenly dull philosophy classes of Concord. Jones rallied his friends and together they started The American Akademe on July 2, 1883. Jones thought they could get four hundred members scattered across the continent, and he believed that many American Platonists would be enough to influence American culture and improve the prospects of the republic, as he wrote to a friend.

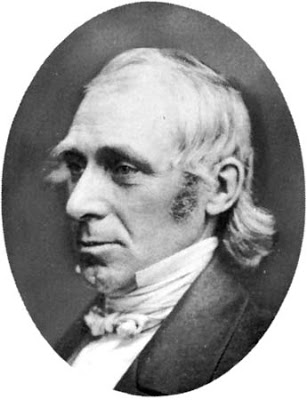

Bronson Alcott, one of the three amigos of American Transcendentalism.

Concord was a summer school. The American Akademe was a winter school, ten meetings a year, from September to June. At first the meetings took place in Hiram’s study. But as the membership increased Hiram dedicated a large room in his house to what became known as Akademe Hall. The linoleum floor and simple chairs lining the walls without symbols, paintings or other decor, provided a clean bare space for pondering abstractions. Mrs. Jones would later be fondly remembered for interrupting long winded controversies with wry comments like “Gentlemen, time for some terrestrial refreshments.”

William Jennings Bryan in his autobiography gave us this portrait of Dr. and Mrs. Jones: “My father had a distant relative, a physician of prominence, Dr. Hiram K. Jones, between whom and my father a warm friendship had developed. Dr. Jones was a man of the highest character, of great learning, and lofty ideals. His wife, Cousin Lizzie, as we called her, was one of the sweetest characters, which it has ever been my privilege to know. She was a woman of rare intelligence, fond of literature and music, and was possessed of temper that nothing could ruffle. She was so charitable in her attitude toward others that I do not recall having heard her say an unkind word of anyone during the six years that I made my home in the family. Even a criticism made by others would pain her as if it were directed against her and she would protest with a sincerity that was manifested in both tone of voice and in the expression of pain upon her face. As I view in retrospect my own life in the Jones family I find it difficult to calculate the influence which association with them had upon my ideas and ideals. They had no children and I was only one of a number of schoolboys to whom they had furnished a home.”

By May 1884 there were 180 members of the American Akademe. When the last meeting was held in 1892 the membership list was 422. But some members never attended the monthly meetings since they lived across the American continent from Maine to California, and a few members lived in Mexico, France, Australia and other faraway places. About fifty regulars could be counted on, but that dwindled to thirty in the last few years. The membership included many physicians, college professors, ministers, and an equal number of women. Akademe members wrestled with the problem of fitting evolution into Plato’s vision of the creation and function of the world. They strove to prove the superiority of Plato to Hegel. But the speakers never lost sight of the practical advice for living well they had found in Platonism.

Feuss Rosenbusch microscope from about 1880.

Founder of the Jacksonville Microscopic Society, Hiram brought the latest microscopes from Europe, demonstrated them at the college and allowed other doctors to use them. He became a charter member of the town’s Literary Society. Hiram was professor of philosophy at Illinois College from 1886 to 1900. He was president of the Illinois College Board of Trustees for a decade. At the business college he sometimes lectured on anatomy and physiology. He helped maintain a deer park near town, and recorded the location of every artesian well in the area, as a public service.

But then in 1891 Mrs. Jones died. Hiram never really recovered. Jones was not in the best health himself and already had too many responsibilities as a practicing physician and a professor at Illinois College. The Akademe limped on another year with a watered down program including classes on Homer and ancient Greek drama. Within two years the Plato Clubs, the American Akademe, The Bibliotheca Platonica journal, the Journal of Speculative Philosophy and the Journal of the American Akademe disappeared. Pragmatism and materialism, new American philosophies driven by industrial capitalism and the achievements of science became the professional standard.

Hiram showed his devotion to Illinois College in his last years giving generous gifts. In 1895 for a new library and chapel he gave twenty thousand dollars. The money he was owed for his loan, an annuity, he waived. The building was named Jones Memorial Hall in memory of his wife. He gave another ten thousand dollars in 1902 the year before he died, and in his will bequeathed the college almost forty thousand more, and his library.

Despite reports of his ever-stained vest, and his obstinate opposition to the theory of infection by germs, Hiram was remembered as an exemplary physician. According to his obituary in the 1903 Illinois Medical Journal “his constant endeavor was to thoroughly comprehend the psychic, spiritual and physical natures of man.” (In the obituary psychic is misspelled phychic). The Journal adds: “This Society will cherish the memory of Hiram K. Jones because of his clean, devoted, scholarly, manly and blameless record as a physician. It would urge upon all physicians to follow his example and make intrinsic worth of character with painstaking adherence to the professional ideals, as the true foundation, for success in the practice of medicine.”

Americans who had flocked to literary clubs now joined service organizations. Professional sports, and weekend sports for everyone, became the most popular American pastimes. A new generation of intellectuals spurned grandma’s Plato Club, preferring societies devoted to science. As the last embers of the Midwestern Platonists went out talkies launched a new generation of movie stars. America’s flirtation with paganism continued but wisdom was no longer the attraction. In 1920 a tourist in San Francisco wrote about a less cerebral form of pagan renaissance, a religious spectacle by an organization calling itself a church: “The priest and priestess sitting in two gold chairs with the twelve vestal virgins as the choir. Behind them was a great illuminated cross with flashing lights. During the service, the very lightly clad vestal virgins threw flowers among the audience. It was a scream. Afterwards came the Love Feast. A virgin held a basket of bread and the audience was asked to join the holy order, which was non-sectarian. Another virgin held a loving cup of wine. Talk of hypnosis, would you believe it, over one hundred and fifty people went forward and partook of that sacrilegious feast.”

Though Plato may not have been popular, the world was in the blush of faith in a world after war that owed much to Platonic ideas about utopia. Several famous American mediums warned that a world war more terrible than the first was just around the corner. Their pessimism was ridiculed. By the time the Great Depression began in 1929 the Plato Clubs were a quaint memory like wooden sidewalks.

PAGAN PHILOSOPHERS OF THE PRAIRIE

Restored Illinois prairie.

But what does all that have to do with the The Platonist? Thomas Moore Johnson was the plucky fellow who decided what the Midwest needed was a magazine about Plato. Even as a young man Johnson, because of his large library and his dedicated study of Platonism, was recommended by Alcott and others as the scholar to turn to on obscure questions about the subject. His early translations were dreadful, but they improved over time. Johnson gave his law practice just enough attention to keep his scholarly pursuits funded. He collected the best Platonic library in America at the time, a collection so large he had a building made for it. Hiram K. Jones was aside from Johnson himself one of the most consistent contributors to The Platonist of not only writing but also money and promotion.

In 1882 Jones wrote Johnson to tell him he had given away six hundred copies of the first issue of The Platonist but subscriptions were few and far between. Jones proposed various ways to raise money to keep the Platonist going. Johnson proposed a higher subscription price but Jones thought that was a mistake. The second volume of The Platonist was delayed. In 1883 when the American Akadame was established in Jacksonville, Jones promised Johnson fifty new subscribers. Johnson wasn’t interested until Jones came up with the idea of publishing all papers by the Akademe in The Platonist. That way all the members would be likely to subscribe. That got Johnson motivated. But subscribers were still scarce and soon Jones was sending Johnson more money to keep The Platonist going. Jones thought it should be turned over to the Akadame and renamed Philosophy. Johnson could stay on board as editor and director. Johnson refused. The Akademe began publishing its own journal.

They remained friends, and Jones continued to help Johnson however he could. A note in the 1889 volume of The Platonist records the celebration of Plato’s birthday on November 7, 1888, a tradition the participants hoped would not only become a yearly event, but someday a national, or even international holiday. Jones participated. The Platonist reported: “Dr. Hiram K. Jones, of Jacksonville, Illinois, who declared that his “lucid interval” was in the morning, rather than in the evening, delivered a most eloquent extemporaneous discourse on the “Symposion of Plato.”

The Platonist never really got off the ground. In part 3 of this series the story will be told in detail of its surprisingly profound influence despite the near disappearance of the few issues published. Short of money, struggling with bad health, Johnson was only able to issue the magazine sporadically. Toward the end he downsized it and added articles about the occult and asian mysteries hoping to attract Theosophical subscribers, but that was a short-lived experiment. He launched a new magazine with an even more ponderous name: Bibliotheca Platonica. His restored purity of purpose found few subscribers and only four issues were published.

Looking to the past, the Platonists of the Midwest would have been right at home with John Winthrop Jr. and the Intelligencers of early colonial America, they had many of the same books in their libraries. Looking to the future, Manly P. Hall and his Philosophical Research Society would have fit right in with the Plato Club and the American Akademe. Not only were their goals similar, but also the recommended course of study featured many of the same authors. Manly Hall and Alexander Wilder even agreed on the likelihood of Francis Bacon having something to do with the original Rosicrucians. Because of American Metaphysical Religion in many ways they had more in common with each other than the very different times they lived in.

Living in the desert climate of Los Angeles has taught me how rough dry heat is on books. I enjoyed reading The Platonist for several years. But the pages became so delicate they would tear if turned. I realized the book would disintegrate under my care. I had to give it up so it could be stored properly. I sold it to William Dailey, an icon of the southern California rare book community. I knew he’d find a good home for it.

Next this series will explore Alexander Wilder, who was widely known as the Walking Encyclopedia. A physician as well as a professor of philosophy with a penchant for archeology, not only was he the most dedicated collaborator of Hiram K. Jones, but also of Thomas Johnson. Wilder was an important and regular contributor to The Platonist. He was also such an important editor and mentor for Helene Blavatsky in her creation of Isis Unveiled that a few authors have argued that he deserves to be given credit for writing that classic of Theosophy.

Part three will tell the story of Thomas Moore Johnson, the editor and publisher of The Platonist, a shy bookish fellow described by one acquaintance as looking like Ichabod Crane, the near sighted, hard of hearing scholar it appears may also have been a founder of a group practicing ceremonial magic in the American Midwest.

Part four will look at the life of Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie, born late, he missed all but the very end of the 19th century Platonic party but struggled on anyway, translating Neoplatonic classics, complaining that academia was ignoring his scholarship, but nevertheless undermining his self published books by including in them his own hilarious and undignified advertisements that had more to do with the good ol’ American hard sell than ancient Greek metaphysics.

This is part one of a four part series.

The Platonist on Sunset Blvd 1: Hiram K. Jones the Western Wonder

The Platonist on Sunset Blvd 2: Alexander Wilder the Walking Encyclopedia

The Platonist on Sunset Blvd 3: The Midwest Needs a Magazine about Plato

The Platonist on Sunset Blvd 4: K.S. Guthrie Explains it All to You! Yes, You!

Sources:

Hiram K. Jones and Philosophy in Jacksonville

Anderson, Paul

Journal of the Illinois Sates Historical Society

Vol. 33, No. 4. Dec. 1940

Platonism in the Midwest

Anderson, Paul

Temple University Publications 1963

Alcott and the Concord Summer School

Bregman, Jay

Alexandria 5: The Journal of Western Cosmological Traditions

Phanes Press 2000

Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan:

By Himself and His Wife

Winston Co. 1925

Numenius of Apamea:

The Father of Neoplatonism

Guthrie, Kenneth Sylvan

Comparative Literature Press 1917

Plotinus: Chronologically Translated

Guthrie, Kenneth Sylvan

George Bell and Sons 1918

“Toward the Holy Land: Platonism in the. Middle West”

Harper, George Mills

South Atlantic Modern Languages Association. XXXII:2 (March 1967)

The Peerless Leader William Jennings Bryan

Hibben, Paxton

Farrar and Rinehart 1929

Obituary of Hiram K. Jones

Illinois Medical Journal

vol. 5-6, 1903. p. 173

Mark R. Jaqua’s comprehensive online collection of writing by and about Alexander Wilder.

New and Alternative Religions in America: Volume 5

Traditions and Other American Innovations

Ashcraft and Gallagher, eds.

Greenwood, 2006

The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor:

Initiatic and Historical Documents of an Order of Practical Occultism

Godwin, Chanel, Deveney eds.

Red Wheel/Weiser 1995

Mystics and Messiahs:

Cults and New Religions in American History

Jenkins, Philip

Oxford University Press 2000

New England Transcendentalism and St. Louis Hegelianism

Pochman, Henry

Haskell House 1948

The Influence of Egypt on the Modern Western Mystery Tradition:

The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor

Scarborough, Samuel

Journal of the Western Mystery Tradition

No. 1, Autumnal Equinox 2001

Esoteric Origins of the American Renaissance

Versluis, Arthur

Oxford University Press, 2001

Written by Ronnie Pontiac

Newtopia staff writer RONNIE PONTIAC is a founding member and primary guitarist of Lucid Nation, executive producer of the documentaries Rap is War, Exile Nation, and the award winning animated short Cohen on the Bridge. He associate produced The Gits documentary, and was art editor, then poet in residence for Newtopia Magazine in its former incarnation . He’s a published author of works on obscure topics such as ancient Greek religion and the history of alchemy. Follow him on Twitter @AmerMysteries.

Thomas Moore Johnson named his son Waldo Plato after his father Waldo Porter Johnson and of course, the philosopher Plato. Sending this bit of Johnson trivia, I’m Lawrence Lewis, Osceola, Missouri. In the interests of disclosure, Waldo Plato Johnson married Katherine Lewis, a first cousin of my father’s.

Posted by Lawrence Bernard Lewis | October 23, 2013, 11:19 amAmazing and surprisingly new info to me at 57years of age because I am:

1-From Jacksonville, IL.

2-A graduate of Illinois College.

3-An MD and amateur philosopher myself.

Based on a mention in Chet Raymo’s “Science Musings” blog-was reading the book “Eden’s Outcasts” concerning Louisa May Alcott and her father Bronson. A mention of Bronson’s connection with Hiriam Jones/Jacksonville/The Plato Club and here I am.

Thanks very much for a well-written and enlightening post!

Posted by Danny Ray | October 4, 2014, 3:10 pm